Diabetes & Prediabetes Tests

This content compares the following tests

- fasting plasma glucose (FPG) test

- oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

- A1C test

- random plasma glucose (RPG) test

These tests may be used to screen for and diagnose diabetes and to detect individuals with prediabetes.1

Confirming diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is definitively made by blood tests. Diagnosis requires two abnormal test results from the same sample or from two different samples. Repeat the test using one of the following methods

- Repeat the same test or run a different test.1 The second test should be done immediately.1

- If two test results indicate diabetes, consider the diagnosis confirmed.1

- If the two different tests conflict, repeat the test that is above the diagnostic threshold. Diagnosis is made based on the confirmed test.1

If the patient’s diabetes test results are close to—but not within—the diagnostic range of the test, the patient may have prediabetes. Health care professionals may wish to observe patients with prediabetes whose condition is likely to progress, recommend lifestyle modifications, and retest in 3 to 6 months.1

Interpreting laboratory results

When interpreting laboratory results, health care professionals should

- consider that all laboratory test results represent a range, rather than an exact number2

- know the A1C assay methods used by their laboratory1

- send blood samples to be tested by a laboratory that uses an A1C analysis method certified by the NGSP to ensure the results are standardized to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay1

- consider the possibility of interference in the A1C test when a result is below 4%, above 15%, or is at odds with other diabetes test results1

- consider each patient’s profile, including risk factors and history, and individualize diagnosis and treatment decisions in discussion with the patient1

Comparing diabetes blood tests

View the content below as a table in the PDF version (PDF, 582.72 KB) .

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) test

Uses

- Screening and diagnosis of prediabetes1 or impaired fasting glucose (IFG)

- 100–125 mg/dL3

- Screening and diagnosis of diabetes1

- 126 mg/dL or higher1

- repeat for confirmation of diagnosis

Technical features2

- Diagnosis requires a lab test; meter results are not suitable

- Sample in morning, after 8-hour fast1

- Sample: sodium fluoride plasma preferred

- Sample stability: low—requires processing within 30 minutes

- Sensitivity: greater than the A1C test, less than the OGTT

- Coefficient of variation: assay variability

- Biological variability

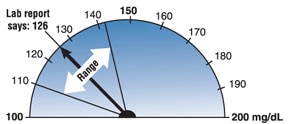

With a coefficient of variation of 5.7% (typical biological variation within the same person), an FPG test result of 126 mg/dL could indicate a true FPG of anywhere from approximately 110 to 142 mg/dL.2 Image courtesy of David Aron, M.D., Louis Stokes Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

| Pros | Cons2 |

|---|---|

|

|

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

Uses

- Screening and diagnosis of prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)1

- 140 to 199 mg/dL at 2 hours1

- Screening and diagnosis of diabetes1

- ≥200 mg/dL or higher at 2 hours1

- repeat to confirm the diagnosis

Technical features

- Performed as described by the World Health Organization (WHO), using a glucose load containing the equivalent of 75 grams of anhydrous glucose dissolved in water1

- Sample in morning: two samples after 8-hour fast and 2 hours after glucose load4

- Sample stability: low—requires processing within 30 minutes

- Patients should ingest at least 150 grams/day of carbohydrates for 3 days before test2

- Sensitivity: greater than the A1C or the FPG tests

- Range of variability: 16.7%2

| Pros2 | Cons2 |

|---|---|

|

|

A1C test

The A1C test is sometimes called the hemoglobin A1C, HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin, or glycohemoglobin test.

Uses

- Screening and diagnosis of prediabetes1

- 5.7–6.4%1

- Screening and diagnosis of type 2 diabetes1

- 6.5% or higher1

- repeat for confirmation of diagnosis

- Monitoring of diabetes

Technical features

- Diagnosis requires a laboratory test certified by the NGSP and standardized to the DCCT assay.1 Some point-of-care A1C assays may be certified by the NGSP or approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis; however, they should only be considered in laboratories that are certified to perform moderate-to-high complexity tests to ensure testing proficiency.1

- Sample at any time of day, no fasting required3

- Sample: anticoagulated whole blood

- Sample stability: superior5

- Sensitivity: less than the FPG test and the OGTT1

- Coefficient of variation: for between laboratory assay variability, see College of American Pathologists (CAP) survey data

| Pros | Cons* |

|---|---|

|

|

Random plasma glucose (RPG) test

Uses

- Diagnosis of diabetes—used only with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis

- polyuria, polydypsia, and unexplained weight loss

- 200 mg/dL or higher1

Technical features

- Sample at any time, no fasting required3

- Sample stability: low—requires processing in less than 30 min

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Comparing diagnoses

In some people, a blood glucose test may indicate a diagnosis of diabetes even though an A1C test does not.1

The reverse can also occur—an A1C test may indicate a diagnosis of diabetes even though a blood glucose test does not.1

Because of these variations in test results, health care professionals should repeat tests before making a diagnosis. People with differing test results may be in an early stage of the disease, where blood glucose levels have not risen high enough to show on every test.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Randie Little, Ph.D., NGSP, University of Missouri School of Medicine, and David B. Sacks, M.B., Ch.B., F.R.C.Path., NIH Clinical Center