Teens, Genes, and Food Choices: What Contributes to Adolescent Obesity?

Health care professionals can help adolescents prevent obesity from becoming an unwanted side effect of the unique growth period they undergo on their way to adulthood.

As a nurse, family nurse practitioner, and investigative researcher for the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Paule V. Joseph NIH external link has worked extensively with individuals with diabetes and obesity. Here she talks about the rise of obesity in adolescents, the diabetes-related health implications, and what we can do to reduce young people’s risk for obesity.

Q: How critical is the issue of adolescent obesity?

A: Based on the current data, almost 21 percent External link (PDF, 588.88 KB) of adolescents ages 12–19 are affected by obesity. The obesity rate among all populations has increased steadily, although there is some evidence, at least with childhood obesity, that it’s starting to level off. But there’s a lot that needs to be done to decrease the amount of childhood and adolescent obesity.

Q: For adolescents, what risk does obesity pose for acquiring type 2 diabetes?

A: There's plenty of evidence that has linked obesity to type 2 diabetes. Teens and even younger children who have obesity are at a higher risk. They develop insulin sensitivity and you start to see changes in their hemoglobin A1C. When you see this, it’s important to intervene with nutrition information, because there might still be time to prevent type 2 from developing. This is very important, because the consequences of type 2 diabetes and the comorbidities associated with it are so detrimental to health.

Q: Is the prevalence of adolescent obesity the same across races and ethnicities?

A: Prevalence is highest among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic youth. This, of course, puts them at higher risk for comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, early cancer, and other disorders that have been associated with obesity.

Q: What is it about adolescents that makes them different from adults in terms of obesity risk?

A: We have all been adolescents, so we know about the changes that happen to our bodies during that time. Adolescents are growing, so they need more calories. However, it’s the source of those extra calories that can be the problem. We are seeing that consuming excess sugar and fat is putting adolescents at higher risk of developing obesity.

Besides the rapid growth that they are experiencing, adolescents are also undergoing changes in brain development. They are starting to make their own choices about whether to eat foods that are good or bad, and they’re experiencing a lot of peer pressure with those decisions. They’re also experiencing hormonal changes that might give them stronger cravings for certain foods.

During adolescence, you would expect there to be increased physical activity, but in the era in which we are living, a lot of adolescents are actually quite sedentary. For example, many are spending a lot of time playing sedentary video games instead of being active.

These are all reasons why we need prevention efforts and new interventions that can decrease the risk for adolescent obesity. But one of the big gaps in the literature is studies focused on adolescents; a lot of obesity studies lump them together with younger children. Adolescents are not children and they’re not adults—they are a unique group, and therefore, we should study them separately.

Q: What are some of the environmental factors affecting adolescent obesity?

A: Socioeconomic status is definitely one of the predictors of obesity. It's interesting because in the United States, we see that adolescents with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to develop obesity while if you look at adolescents in low-resource countries outside the United States, it’s the total opposite—the kids with higher socioeconomic status are more affected by obesity. That could be because in those low-resource countries, money may give access to fast foods. But here, sometimes it’s cheaper to buy fast foods compared to healthy foods.

Another environmental factor, which I alluded to earlier, is the influence of friends. It’s like, “My friend is drinking a soda. Why can’t I drink one?” Even when adolescents know they have diabetes and are not supposed to drink a soda, sometimes peer pressure affects them.

Having healthy foods available is another environmental factor. Some neighborhoods are food deserts—the availability and accessibility of healthy foods is limited. Also, if you go to the supermarket, all the tempting snacks are placed right at the checkout line. We are visual individuals, so even if you’re not hungry, sometimes you just become hungry when you see these things. Furthermore, we have to look at the food being served in school cafeterias and vending machines.

Environmental factors create incentives and disincentives to get the physical activity that can help manage obesity. The American way of life is less set up for walking—such as to a school, for errands, or to get to a job—than ever before. Urban planners are trying to create more walkable environments, but as a country we’re not there yet. Young people today also may get less physical activity if their environment does not provide them access to gyms, parks, playgrounds, and other safe places to move around, or if they cannot afford recreational activities or equipment.

And, of course, there are cultural differences. We have adolescents who are fourth and fifth generation Americans, but we also have those who have just arrived in the country. In groups new to the country, you can see changing trends in their eating habits as they adapt to this culture, which parallels trends in weight gain. This ties back to those pressures we just discussed.

Recently, there have been several studies on sleep. An adolescent’s chronotype—their innate preferences for waking and sleeping—influences not only their sleep patterns, but also the way their body processes foods. So, their sleep schedule, and how well it fits with their chronotype, may affect weight. Furthermore, an adolescent’s school and activity schedule may not provide time for physical activity and can cause stress, which is linked with obesity.

Q: What is known about genetic influences on obesity?

A: Several genes have been associated with higher risk for obesity. Genetic variables have been associated with body size, body mass index, waist circumference, appetite, and more.

We used to be taught that the genes that you were born with are the genes that you are stuck with. However, now we know that the environment influences the genome, creating epigenetic changes that affect obesity. Therefore, it’s very important to study the adolescent group separately from children or adults. We know that you are born with certain genes, but we also understand that the environment affects and interacts with our genes. So ultimately, it is the combination of our genes and our environment that determine our health. For example, eating healthy foods may reduce our genetic risk for disease.

Q: What further research do you think needs to be pursued on the topic of adolescents and obesity?

A: We need to learn more about applying precision medicine to obesity. How can we use zip code data, other data from patients’ medical records, gene sequencing, and so forth, to create a more personalized model of treatment? Preventing and treating obesity is not one-size-fits-all. We need more studies separating younger children from adolescents, so that we can really understand this unique population.

Q: What can health care professionals do to prevent and treat obesity in their adolescent patients?

A: It's very important to be aware of the evidence that is emerging about obesity, despite the gap between the research and application of this knowledge in clinical practice.

You can get families involved in various ways. For example, you can have nutrition talks while you're doing your physical assessments—taking time to ask, “What it is that you’re eating?” We clinicians do a lot of assessments, such as well-child checks, but we need to screen not only for obesity, but also for what they are eating. That way, we can actually intervene earlier before the adolescent develops type 2 diabetes.

Also, motivational interviewing can help. Provide examples of people who were on a weight-gain trajectory before and how they have taken control of their health. You also can provide visual examples, such as a model of fat, which is easily obtained on the Internet, to show your patients what it looks like and to say, “This is being stored in your body.” This can be influential in terms of a young patient’s decision making. Sometimes they’ll say, “I don't want that to happen to me.”

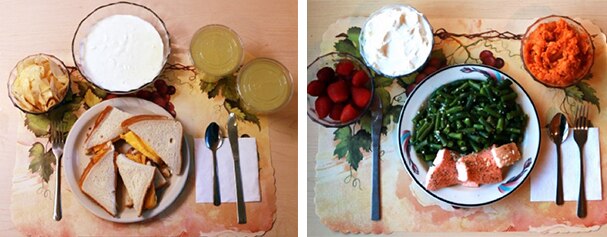

As another example, a randomized control trial conducted by NIDDK researcher Dr. Kevin D. Hall studied the impact of eating unprocessed versus ultra-processed foods, and the published study results External link includes pictures of menus. I have clinician friends who have taken those pictures and put them up in their waiting rooms, so by the time patients go into an exam room, they’re already saying, “I'm not supposed to have chips, because that’s a processed food.”

Figure 1. Ultra-processed lunch (left), unprocessed lunch (right)

Figure 1. Ultra-processed lunch (left), unprocessed lunch (right)You can encourage your young patients to incorporate more physical activity into things they already like to do. If they like video games, for example, they can be encouraged to try active video games, or “exergames.” The National Institutes of Health has sponsored some promising research into the health benefits of this activity. As another idea, some teens may be motivated by competing with themselves or their friends on how many steps they can take in a day, using step-counting devices. This is an exciting area of current research.

I do think it’s important to know the population that you’re taking care of, know what has worked, and try some of those things. For example, my colleagues and I wrote a paper, Adolescent Obesity in the Past Decade: A Systematic Review of Genetics and Determinants of Food Choice NIH external link, that reviewed a total of 41 full-text articles that contained studies limited exclusively to adolescents. It’s generated a lot of discussion and I encourage health care professionals to read it.

Editor’s Note: Health care professionals are encouraged to share with adolescent patients and their families these two resources:

Comments