Prolactinoma

On this page:

- What is a prolactinoma?

- How common are prolactinomas?

- Who is more likely to develop a prolactinoma?

- What are the complications of having a prolactinoma?

- What are the symptoms of having a prolactinoma?

- What causes prolactinomas?

- How do doctors diagnose prolactinomas?

- How do doctors treat prolactinomas?

- How do doctors treat prolactinomas during pregnancy?

- Clinical Trials for Prolactinoma

What is a prolactinoma?

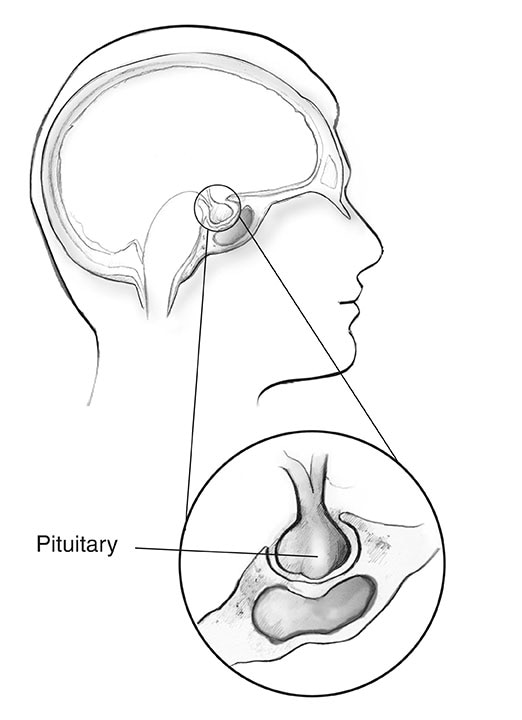

A prolactinoma is a benign (noncancerous) tumor of the pituitary gland that produces a hormone called prolactin. Located at the base of the brain, the pituitary is a pea-sized gland that controls the production of many hormones.

Prolactin signals a woman’s breasts to produce milk during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Having too much prolactin in the blood, a condition called hyperprolactinemia, can cause infertility and other problems. In most cases, prolactinomas and related health problems can be successfully treated with medicines.

The pituitary gland sits at the base of the brain.

The pituitary gland sits at the base of the brain.How common are prolactinomas?

Small, benign pituitary tumors are fairly common in the general population. A prolactinoma is the most common type of pituitary tumor, making up about 40 percent of all pituitary tumors.1

Who is more likely to develop a prolactinoma?

Women are more likely than men to develop a prolactinoma. These tumors rarely occur in children and adolescents. In children, prolactinomas may prevent the start or block the progression of puberty.

Prolactinomas occur more often in women than men.

Prolactinomas occur more often in women than men.What are the complications of having a prolactinoma?

Having a prolactinoma can lead to different symptoms and problems among women and men. Some of these are caused by having too much prolactin in the body, while others are linked to the size and location of the tumor.

Excess prolactin, or hyperprolactinemia, can lower levels of sex hormones in both women and men. Related complications can include

- infertility

- bone loss (osteoporosis)

Prolactinomas are usually small, less than 1 centimeter in diameter. These small tumors are called “microprolactinomas.” Less commonly, a tumor may grow to more than 1 centimeter in diameter. These larger tumors are called “macroprolactinomas.” Macroprolactinomas may press against nearby parts of the pituitary gland and the brain. Complications can include

- vision problems, caused when the tumor presses on the optic nerves or optic chiasm, the part of the brain where the two optic nerves cross over each other

- headaches

- low levels of other pituitary hormones, such as thyroid hormones and cortisol

What are the symptoms of having a prolactinoma?

Among women, common symptoms of having a prolactinoma include

- changes in menstruation, such as irregular periods or no periods

- infertility

- milky discharge from the breasts, also called galactorrhea

- loss of interest in sex

- pain or discomfort during sex due to vaginal dryness

Among men, common symptoms include

- loss of interest in sex associated with low levels of testosterone

- erectile dysfunction

Women often report symptoms earlier than men because they may notice changes in their periods or milky discharge from their breasts when they are not pregnant or breastfeeding. But women who are taking sex hormones—in birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy—may not experience these changes.2 The same is true for women who have reached menopause and no longer have periods. Among these women, and among men, a lack of clear signs and symptoms may lead to a delayed diagnosis.

What causes prolactinomas?

Most pituitary tumors develop on their own. The cause of these tumors is unknown. In some cases, genetic factors may play a role. For example, the inherited disorder multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 increases the risk for prolactinomas.

What else can cause prolactin levels to rise?

Prolactin levels normally rise during pregnancy and breastfeeding. They may also rise slightly at other times because of1

- physical stress, such as a painful blood draw

- exercise

- a meal

- sexual intercourse

- nipple stimulation

- injury to the chest area

- epileptic seizures

These increases in prolactin are usually small and temporary. Other than a prolactinoma, the factors that most often lead to excess prolactin in the blood are medicines, illnesses, and other pituitary tumors.

Medicines. The brain chemical dopamine helps curb the production of prolactin in the body. Any medicine that affects the production or use of dopamine can make prolactin levels rise.

Medicines that can increase prolactin levels include some types of

- antipsychotic medicines, such as risperidone, but not others, such as clozapine3

- high blood pressure medicines

- drugs used to treat nausea and vomiting

- pain relievers that contain opioids

Although the hormone estrogen stimulates the release of prolactin, estrogen-containing birth control pills and hormone replacement therapy have not been found to cause hyperprolactinemia.4

If high prolactin levels are because of a medicine, these levels will usually return to normal 3 to 4 days after the drug is stopped.

Other illnesses. Illnesses that may increase prolactin levels include

- kidney disease

- an underactive thyroid, or hypothyroidism

- shingles—particularly when lesions affect your chest

Other pituitary tumors. Other large tumors located in or near the pituitary gland may also raise prolactin levels, usually by preventing dopamine from reaching the pituitary gland.

Sometimes the cause of excess prolactin is unknown.

How do doctors diagnose prolactinomas?

Doctors diagnose prolactinomas based on the results of two tests

- Blood test. The prolactin blood test will measure the level of prolactin in your blood. If the level is too high, your doctor will order an imaging test to detect a possible tumor.

- Imaging tests. The preferred test is the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which uses radio waves and magnets to create detailed images of your internal organs and soft tissues without x-rays. If an MRI is not a good option for you (for example, if you have a pacemaker or other implant that has metal), your doctor may order a computed tomography (CT) scan instead. The results of the imaging test usually will allow your doctor to confirm a diagnosis of prolactinoma and determine its size and location.

A blood test is used to detect high levels of prolactin.

A blood test is used to detect high levels of prolactin.

After confirming the prolactinoma diagnosis, your doctor may conduct other tests to find out if the tumor is affecting other hormones. Depending on the tumor’s size, your doctor may also ask you to take a vision test.

How do doctors treat prolactinomas?

Doctors commonly treat prolactinomas with medicines. More rarely, surgery or radiation therapy may be used. The goals of treatment are to

- bring prolactin levels back to normal

- shrink the tumor

- make sure the pituitary gland is working properly

- correct any problems caused by the tumor, such as menstrual problems, milky discharge from the breasts, low testosterone levels, headaches, or vision problems

Medicines

Medicines called dopamine agonists control prolactin levels and shrink the tumor very effectively. These drugs mimic the effects of the brain chemical dopamine.

Two dopamine agonists are most commonly used to treat prolactinomas

- bromocriptine, a drug that must be taken twice or three times daily

- cabergoline, a drug that can be taken once or twice per week

Cabergoline is the preferred drug for treating prolactinomas, because it is more effective than bromocriptine and has fewer side effects.1

Outcomes. For most small prolactinomas, dopamine agonists bring prolactin levels back to normal and shrink tumors in 4 out of 5 patients.5

Side effects. Common side effects of the drugs include nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Both medicines should always be taken with food. Starting treatment at a low dose and taking the medicine at bedtime can reduce side effects.

Complications. Although dopamine agonists have been linked to heart valve damage, these problems were found mainly among people taking these medicines to treat Parkinson’s disease. These patients typically take much higher doses (usually about 10 times higher) of these medicines than are used to treat prolactinomas. If you need to take a high dose of a dopamine agonist, your doctor may order an echocardiogram (echo) to check your heart valves and heart function. Rarely, psychiatric disorders related to impulse control, such as compulsive gambling, have been seen in people taking these medicines.6

Duration of treatment. You may have to take these medicines for a long time to prevent the tumor from growing back, especially if the prolactinoma is large. After 2 years, the medicines may be slowly reduced and stopped if prolactin levels are normal and the tumor is no longer visible.1 But if your prolactin level goes back up again, you may need to go back on the medicine for as long as needed to bring your prolactin level under control.

Surgery

Although doctors most often treat prolactinomas with medicines, in some cases surgery may be an option. Examples include

- you can’t tolerate the medicines

- the medicines aren’t working for you

- you take antipsychotic medicines that interact with the medicines used to treat prolactinomas

In some cases, when a prolactinoma is large, a woman may choose to have surgery to remove the tumor before trying to become pregnant.

Two types of surgery may be used

- Transsphenoidal surgery is most commonly used to treat prolactinoma. The surgery is done through an incision, or cut, at the back of the nasal cavity or under the upper lip.

- Transcranial surgery is used more rarely if the tumor is large or has spread to other areas. The surgeon removes the tumor through an opening in the skull.

Outcomes. The success of the surgery depends on many factors, including

- skill and experience of the surgeon

- size and location of the tumor

When done by an experienced surgeon, the surgery corrects prolactin levels in about 90 percent of people with small tumors and 50 percent of those with large tumors.7 For people with larger prolactinomas that can only be partly removed, medicines often can return prolactin levels to a normal range after surgery.

Side effects and complications. Side effects of the surgery can include

- low pituitary function, or hypopituitarism

- temporary diabetes insipidus, a condition that leads to frequent urination and excessive thirst

- cerebrospinal fluid leak

- local infection

Radiation

More rarely, if medicines and surgery fail to reduce prolactin levels, radiation therapy may be used. This type of treatment uses high-energy x-rays or particle waves to kill tumor cells. Depending on the size and location of the tumor, the total radiation dose is delivered in one session, or in lower doses over the course of 4 to 6 weeks.

Outcomes. Prolactin levels return to normal in 1 out of 3 patients treated with radiation therapy.1 However, as radiation treatment lowers prolactin levels over time, it may take years to reach this outcome. Your doctor is likely to prescribe medicines while you wait to see results.

Side effects and complications. The most common side effect is low levels of thyroid hormone. In up to half of patients, radiation therapy may also lead to a decrease in other pituitary hormones.8 Vision loss and brain injury are rare complications. Rarely, other types of tumors can develop many years later in areas that were in the path of the radiation beam.

How do doctors treat prolactinomas during pregnancy?

Before pregnancy. Having a prolactinoma may make it difficult for you to become pregnant, but treatment with dopamine agonists is very effective in restoring fertility.

Use of dopamine agonists is usually stopped once a pregnancy is confirmed.

Use of dopamine agonists is usually stopped once a pregnancy is confirmed.

When pregnancy is confirmed. Although studies suggest that both bromocriptine and cabergoline can be safely taken in the early stages of pregnancy, bromocriptine is typically preferred because of its longer safety record.1 As soon as your pregnancy is confirmed, your doctor will usually advise you to stop taking these medicines to prevent any possible effects on the fetus.

During pregnancy. Prolactin levels normally increase during pregnancy, preparing your breasts to make milk after your baby is born. The pituitary gland often doubles in size during pregnancy. Your prolactinoma may also grow in size, especially if it is already large. If you begin to have symptoms such as headaches and changes in vision, your doctor may recommend that you start taking the medicine again.

After delivery. After delivery, women with small prolactinomas can usually nurse their babies. If your prolactinoma is large, your doctor may suggest that you consult with an endocrinologist about breastfeeding.

Doctors don’t usually measure prolactin levels during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Your doctor will usually begin to do so again a couple of months after you stop nursing. In some cases, prolactin levels remain normal after delivery and nursing.9

Clinical Trials for Prolactinoma

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including endocrine diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for prolactinoma?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of prolactinoma, including new treatments for this condition.

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

What clinical studies for prolactinoma are looking for participants?

You can view a filtered list of clinical studies on prolactinoma that are open and recruiting at ClinicalTrials.gov. You can expand or narrow the list to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care professional before you participate in a clinical study.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Andrew R. Hoffman, M.D., VA Palo Alto Health Care System and Stanford University School of Medicine