Liver Transplant

- Definition & Facts

- Transplant Process

- Transplant Surgery

- Living with a Liver Transplant

- Clinical Trials

Definition & Facts

In this section:

- What is a liver transplant?

- How common are liver transplants?

- When do people need a liver transplant?

- What are the types of liver transplant?

- What are the survival rates after a liver transplant?

What is a liver transplant?

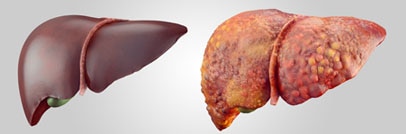

A liver transplant is surgery to remove your diseased or injured liver and replace it with a healthy liver from another person, called a donor. If your liver stops working properly, called liver failure, a liver transplant can save your life.

How common are liver transplants?

In 2015, about 7,100 liver transplants were performed in the United States. Of these, almost 600 were performed in patients 17 years of age and younger.1

When do people need a liver transplant?

People need a liver transplant when their liver fails due to disease or injury.

For adults in the United States, the most common reasons for needing a liver transplant in 2016 were1

- alcoholic liver disease

- cancers that start in the liver combined with cirrhosis

- fatty liver disease (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis)

- cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis C

Biliary atresia is the most common reason children need a liver transplant.1

Doctors may consider a liver transplant to treat rare disorders such as urea cycle disorders and familial hypercholesterolemia.

People may also need a liver transplant due to acute liver failure. Acute liver failure is an uncommon condition most often caused by taking too much acetaminophen.2 Other causes of acute liver failure include

- bad reactions to prescription medicines, illegal drugs, and herbal medicines

- viral hepatitis

- toxins

- blockage of the blood vessels to the liver

- autoimmune diseases

- genetic disorders

What are the types of liver transplant?

Deceased donor transplants

Most livers for transplants come from people who have just died, called deceased donors. During a deceased donor transplant, surgeons remove your diseased or injured liver and replace it with the deceased donor’s liver. Adults typically receive the entire liver from a deceased donor. However, surgeons may split a deceased donor’s liver into two parts. The larger part may go to an adult, and the smaller part may go to a smaller adult or child.

Living donor transplants

Sometimes a healthy living person will donate part of his or her liver, most often to a family member who is recommended for a liver transplant. This type of donor is called a living donor. During a living donor transplant, surgeons remove a part of the living donor’s healthy liver. Surgeons remove your diseased or injured liver and replace it with the part from the living donor. The living donor’s liver grows back to normal size soon after the surgery. The part of the liver that you receive also grows to normal size. Living donor transplants are less common than deceased donor transplants.

What are the survival rates after a liver transplant?

For patients receiving liver transplants from deceased donors, the survival rates are1

- 86 percent at 1 year

- 78 percent at 3 years

- 72 percent at 5 years

The 20-year survival rate is about 53 percent.3

Your chances of a successful liver transplant and long-term survival depend on your personal situation.

References

Transplant Process

In this section:

- Talk with your doctor about a liver transplant

- Visit a transplant center

- Get evaluated for a liver transplant

- Get approved for a liver transplant

- Get placed on the national waiting list

- Confirm living donor match if you choose this type of liver transplant

The liver transplant process has many steps, including talking with your doctor, visiting a transplant center, and getting evaluated.

Talk with your doctor about a liver transplant

The first step is to talk with your doctor to find out whether you are a candidate for a transplant. Doctors consider liver transplants only after they have ruled out all other treatment options. However, a liver transplant is not for everyone. Your doctor may tell you that you are not healthy enough for surgery. You may have a medical condition that would make a transplant unlikely to succeed. If you and your doctor think a liver transplant is right for you, your doctor will refer you to a transplant center.

Visit a transplant center

During your first visit to a transplant center, health professionals will provide information about

- the evaluation and approval process

- placement on the national waiting list

- reasons for being removed from the national waiting list

- the waiting period

- how people are selected for liver transplants

- surgery and recovery

- the long-term demands of living with a liver transplant, such as taking medicines for the rest of your life

Get evaluated for a liver transplant

You will go through a series of evaluations at the transplant center, where you will meet members of your transplant team. You may need to visit the transplant center several times over the course of a few weeks or even months.

Your team will ask you about your medical history and perform medical tests. These tests may include

- a physical exam

- blood and urine tests

- tests that provide pictures of organs inside your body, called imaging tests

- tests to see how well your heart, lungs, and kidneys are working

The team will use the results of these tests to tell them

- how likely you are to survive transplant surgery

- what other diseases and conditions you have

- the cause and severity of your liver disease

Your team will find out if you are healthy enough for surgery. Some medical conditions or illnesses can make a liver transplant less likely to succeed. You may not be able to have a transplant if you have

- a severe infection

- alcohol or drug abuse problems

- cancer outside the liver

- serious heart or lung disease

Also, the transplant team will

- find out whether you or your caregivers are able to understand and follow your doctor’s instructions for care after your transplant. They need to be sure you are mentally prepared for caring for a new liver.

- find out whether you have a good support system of family members or friends to help care for you before and after the transplant.

- review your medical insurance and other financial resources. Many financial assistance programs are available to people receiving a liver transplant and their families to help with the cost of the surgery, medicines, and care.

Get approved for a liver transplant

The transplant center’s selection committee will review the results of your evaluation. Each transplant center has its own guidelines about who can get a liver transplant. Transplant centers often post their guidelines on their websites. The centers also follow national guidelines.

Keep in mind that you may choose not to have a transplant even though you have been approved.

Get placed on the national waiting list

If you are approved for a transplant and do not have a living donor, the transplant center will submit your name to be placed on the national waiting list for a liver from a deceased donor. If you have a living donor, the transplant center will not place you on the national waiting list.

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) has a computer network linking all regional organ-gathering organizations—known as organ procurement organizations—and transplant centers. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a nonprofit organization, runs the OPTN under a contract with the Federal Government. When UNOS officially adds you to the national waiting list, UNOS will notify you and your transplant center.

UNOS policies let you register with more than one transplant center to increase your chances of receiving a liver. Each transplant center may require a separate medical evaluation.

Wait for a match

The waiting period for a deceased donor transplant can range from less than 30 days to more than 5 years.4 How long you will wait depends on how badly you need a new liver. Other factors—such your age, where you live, your blood type and body size, your overall health, and the availability of a matching liver—may make your wait time longer or shorter. The UNOS computer matches a deceased donor’s liver based on your blood type and body size.

UNOS policies rank people with the most urgent need for a new liver to prevent death at the top of the national waiting list.

When a matching liver from a deceased donor is found, your transplant team coordinator will call you right away, tell you what you need to do before going to the hospital, and ask you to come to the hospital right away.

Confirm living donor match if you choose this type of liver transplant

If a family member, spouse, or friend wants to be a living donor, the transplant team will determine whether you and the person have blood types that work together and a similar body size. The transplant team will

- ask the potential donor about his or her medical history

- perform medical tests to make sure the person is in good general health, with no major medical or mental illnesses

The potential donor must be able to understand and follow instructions before and after surgery, be between the ages of 18 and 60, and have an emotional tie to the person receiving the liver transplant.

The OPTN and UNOS provide detailed information on the organ transplant process.

References

Transplant Surgery

In this section:

- How do I prepare for liver transplant surgery?

- How do doctors perform liver transplant surgery?

- What are the possible problems of liver transplant surgery?

- What happens after liver transplant surgery?

- When can I go home after liver transplant surgery?

- When can I go back to my normal activities?

How do I prepare for liver transplant surgery?

How you prepare for liver transplant surgery depends on the type of liver transplant you are having.

- Deceased donor transplant. If you are on the national waiting list for a deceased donor liver, your transplant team coordinator will call you as soon as a matching liver is found. You must go to the hospital right away. Your transplant team coordinator will tell you what you need to do before going to the hospital.

- Living donor transplant. If you are receiving a liver from a living donor, you will schedule your surgery 4 to 6 weeks in advance. Your transplant team coordinator will tell you and the donor what you need to do before going to the hospital for the operations.

How do doctors perform liver transplant surgery?

Doctors perform liver transplant surgery by removing your diseased or injured liver and replacing it with the donor’s liver. Liver transplant surgery can take up to 12 hours or longer. During the surgery, the surgical team will

- give you general anesthesia

- put intravenous (IV) and other types of lines into your body so you receive medicines and fluids

- monitor your heart and blood pressure

If you are getting a liver from a deceased donor, your surgery will start when the donor liver arrives at the transplant center. If you are getting a liver from a living donor, the surgical team will operate on you and your donor at the same time.

What are the possible problems of liver transplant surgery?

Possible problems of liver transplant surgery should be discussed with your surgeon. Some possible problems include

- bleeding

- blood clots in your liver’s blood vessels

- damage to the bile ducts

- failure of the donated liver

- infection

- rejection of the donated liver

What happens after liver transplant surgery?

After your surgery, you will stay in an intensive care unit (ICU). Specially trained doctors and nurses will watch you closely while you’re in the ICU. You’ll begin taking medicines called immunosuppressants to prevent problems with your new liver. The doctors and nurses will perform

- blood tests often to make sure your new liver is working properly

- medical tests to make sure your heart, lungs, and kidneys are also working properly

When your doctors feel you are ready, you will move from the ICU to a regular room in the hospital.

Your transplant team will teach you how to take care of yourself before you get home. Transplant team members will give you information on follow-up medical care, the things you need to do to care for your new liver, and possible problems you may have with your new liver.

After a living donor’s surgery, the donor will stay in a recovery room for a few hours and spend his or her first night in an ICU. Specially trained doctors and nurses will watch the donor closely in the ICU. The day after surgery, the donor will usually move to a hospital room. The doctors and nurses will encourage the donor to get out of bed and sit in a chair the day after surgery and to walk short distances as soon as he or she is able.

When can I go home after liver transplant surgery?

You can likely go home about 2 weeks after your transplant surgery. A living donor can typically go home about 1 week after surgery.

When can I go back to my normal activities?

Your doctor will let you know when you can go back to your normal activities. You can likely return to your normal activities after a few months. Most people are able to return to work, be physically active, and have a normal sex life. You will continue to have regular medical checkups to make sure that your liver is working properly and you have no other health problems. Doctors often recommend that women wait at least a year after their transplant before getting pregnant.

Although recovery times vary, most living donors can often return to their normal activities 1 month after surgery and can return to work within 4 to 6 weeks.

Living with a Liver Transplant

In this section:

- What is organ rejection?

- What are the signs and symptoms of organ rejection?

- How can I prevent organ rejection?

- What are the side effects of immunosuppressants?

- How do I help care for my new liver?

- What should I eat after my liver transplant?

- What should I avoid eating after my liver transplant?

After a liver transplant, you will need to see your doctor often to make sure your new liver is working properly. You will have regular blood tests to check for signs of organ rejection and other problems that may damage your new liver.

What is organ rejection?

Organ rejection occurs when your immune system sees your transplanted liver as “foreign” and tries to destroy it. You have the highest chance of organ rejection in the first 3 to 6 months after your transplant.5

What are the signs and symptoms of organ rejection?

Abnormal liver blood test results may be the first sign of organ rejection. Rejection does not always cause symptoms you may notice. When symptoms of rejection are present, they may include

- feeling tired

- pain or tenderness in your abdomen

- fever

- yellowing of the skin and the whites of your eyes

- dark-colored urine

- light-colored stools

You should talk with your doctor right away if you have symptoms of organ rejection. Your doctor will often perform a liver biopsy to see if your body is rejecting the new liver.

How can I prevent organ rejection?

To help keep your body from rejecting the new liver, you will need to take medicines called immunosuppressants. These medicines prevent and treat organ rejection by reducing your immune system’s response to your new liver. You may have to take two or more immunosuppressants. You will need to take these medicines for the rest of your life.

Rejection can occur any time the immunosuppressive medicines fail to control your immune system’s response to your new liver. If your transplanted liver fails as a result of rejection, your transplant team will decide whether another transplant is possible.

What are the side effects of immunosuppressants?

Immunosuppressants can have many serious side effects. You can get infections more easily because these medicines weaken your immune system. Other possible side effects include

- brittle bones

- diabetes

- high blood pressure

- high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood

- kidney damage

- weight gain

Long-term use of these medicines can increase your chance of developing cancers of the skin and other areas of your body.

Prescription medicines, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and dietary supplements can affect how well immunosuppressants work. Tell your doctor if you are prescribed any new medicines. Talk with your doctor before using over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, dietary supplements, or any complementary or alternative medicines or medical practices.

How do I help care for my new liver?

Do the following to help take care of your new liver.

- Take medicines exactly as your doctor tells you to take them.

- Talk with your doctor before taking any other medicines, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and dietary supplements.

- Keep all medical appointments and scheduled blood draws.

- Stay away from people who are sick.

- Tell your doctor when you are sick.

- Learn to recognize the symptoms of rejection.

- Have cancer screenings as recommended by your doctor.

- Keep up to date with vaccinations; however, “live” vaccines should not be used.

- Talk to your doctor, both before and after your liver transplant, about the use of contraceptives and the risks and outcomes of pregnancy.

Learn how to recognize the symptoms of infection. Symptoms of infection may include:

Talk with your doctor right away if you have symptoms of infection.

Make healthy choices and protect yourself.

- Eat healthy foods, exercise, and don’t smoke cigarettes

- Don’t drink alcoholic beverages or use alcohol in cooking if you have a history of alcohol use disorder.

- Protect yourself from soil exposure by wearing shoes, socks, long-sleeve shirts, and long pants.

- Avoid pets such as rodents, reptiles, and birds.

- Protect yourself against organisms that can transmit diseases, such as ticks and mosquitoes, by

- using insect repellent

- wearing shoes, socks, long-sleeve shirts, and long pants

- not going outdoors at times when organisms are most likely to be active, such as at dawn and dusk

- If you are planning on traveling, especially to developing countries, talk with your transplant team at least 2 months before leaving to determine the best ways to reduce travel-related risks.

What should I eat after my liver transplant?

You should eat a healthy, well-balanced diet after your liver transplant to help you recover and keep you healthy. A dietitian or nutritionist can help you create a healthy eating plan that meets your nutrition and diet needs.

What should I avoid eating after my liver transplant?

Grapefruit and grapefruit juice can affect how well some immunosuppressants work. To help prevent problems with some of these medicines, avoid eating grapefruit and drinking grapefruit juice.

If you have a history of alcohol use disorder, do not drink alcoholic beverages or use alcohol in cooking.

You should avoid consuming the following:

- water from lakes and rivers

- unpasteurized milk products

- raw or undercooked

- eggs

- meats, particularly pork and poultry

- fish and other seafood

Your dietitian or nutritionist may recommend that you limit your intake of

- salt

- cholesterol

- fat

- sugar

References

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Michael R. Lucey, M.D., University of Wisconsin–Madison