News Around NIDDK

Creating a "spellchecker" for genes

By Lisa Yuan

Imagine a pair of molecular scissors that could snip and tweak sections of the genetic alphabet. Or tweezers that could pluck one letter and replace it with another. These tools have become a reality in recent years, allowing scientists to correct “misspellings” in the genetic code.

“Gene editing technologies have taken center stage in biomedical research, with boundless impact on translational medicine,” said Dr. Lothar Hennighausen, chief of NIDDK’s Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology.

CRISPR, which stands for “Clustered, Regularly Interspaced, Short Palindromic Repeat,” works by making cuts at targeted sites on a genome, altering an organism’s DNA. Hennighausen’s lab embraced this budding technology in 2015 and, in collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Transgenic Core Director Dr. Chengyu Liu, has since made key discoveries in gene editing.

In a 2017 Nature Communications study, the team described large, unwanted DNA deletions and insertions associated with CRISPR at the target sites of mammalian genomes. Other scientists followed with similar findings on the random molecular damage that CRISPR can cause at sites targeted for mutations.

But what about CRISPR’s effects outside of targeted sites? Hennighausen’s team studied CRISPR-edited mammalian genomes and concluded that CRISPR did not cause unexpected off-target damage. The findings, published in Nature Methods in October, provided important insight into the safety aspects of CRISPR technology, said Dr. Michaela Willi, lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in Hennighausen’s lab.

More recently, Hennighausen’s lab explored a newer form of gene editing called deaminase base editing. Most known human diseases are caused by mutations in just one of the four letters, or bases, that make up DNA. Base editors can correct these mutations by converting one base pair into another. Unlike conventional CRISPR, they do not cut through the DNA, reducing the chance of unwanted errors.

“The exceptional precision of base editors brings fresh air into the genome engineering toolbox and allows us to avoid problems encountered with conventional CRISPR,” said Hennighausen.

Hennighausen’s team studied the fidelity, or accuracy and reliability, of the two classes of base editors, cytosine base editors (CBE) and adenine base editors (ABE). Their research, published in Nature Communications in November, found that ABEs were more accurate and caused no unintended errors in mouse genomes. In another study, published in Scientific Reports in February, they found that CBEs accurately generated linked mutations – two or more mutations at different sites in the same chromosome – without causing unwanted deletions at target sites in mouse embryos.

Other NIDDK scientists are also applying gene editing to study human disease. Dr. Andy Golden in the Laboratory of Biochemistry and Genetics uses CRISPR to generate mutations in a worm species that shares many of the same genes as humans. By studying how these mutations disrupt gene functioning, Golden and his team hope to identify potential targets for therapy.

And NIDDK’s Genetics of Development and Disease Branch Chief Dr. Richard Proia and Staff Scientist Dr. Maria Laura Allende, together with Dr. Cynthia Tifft of the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Medical Genetics Branch, used gene editing to study Sandhoff disease, a deadly childhood genetic disorder. The researchers used CRISPR to create healthy stem cells to form cerebral organoids, which they compared to Sandhoff-affected organoids to gain greater insight into the disease’s progression.

The Proia and Tifft labs are using gene editing in several current projects, such as correcting point mutations in cells from patients with late-onset Tay-Sachs disease, a neurodegenerative disorder affecting young adults.

Still, while these gene-editing tools hold much promise, applying gene-editing technologies to human health requires a full understanding and thoughtful consideration of their mechanisms, potential negative consequences, and ethical implications. When used responsibly, CRISPR and base editing tools could pave a key pathway to preventing and treating disease.

Longtime division director Dr. Judith Fradkin retires

Fradkin led NIDDK’s Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic DiseasesBy Alyssa Voss

Dr. Judith Fradkin, director of NIDDK’s Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic Diseases (DEM), retired in December after nearly 40 years of service. Her leadership and oversight of research dedicated to the prevention, treatment, and cure of diabetes, and other metabolic and endocrine disorders, improved healthcare for millions of Americans. Around the Institute, Fradkin was known for her attention to detail, ability to think quickly on her feet, broad knowledge, precision in communication, as well as her compassion, collegiality, wit, and generosity.

“Dr. Judy Fradkin truly embodies the NIH mission, and she epitomizes all the qualities we at NIDDK could wish for in a great colleague and leader,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers. “When we see the next great advances in diabetes, endocrinology and metabolic diseases, I hope she knows that she had a major hand in making them happen.”

Fradkin first came to NIDDK as a clinical associate in 1979 after receiving her medical degree from the University of California at San Francisco. She was also an intern and resident at Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital in Boston and an endocrinology fellow at Yale School of Medicine. In 1984, Fradkin became a DEM branch chief and subsequently served in roles as the division’s deputy director and acting director before being appointed as director in 2000.

“Under Dr. Fradkin’s leadership, the Institute launched ambitious clinical trials to advance the prevention and treatment of diabetes, including the TrialNet network to conduct clinical trials to prevent or delay the progression of type 1 diabetes; the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial to compare treatment approaches to type 2 diabetes in children; HEALTHY, a school-based intervention to lower the risk factors for type 2 diabetes in children; the Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes (D2d) study assessing efficacy of vitamin D in type 2 diabetes prevention; the Restoring Insulin Secretion (RISE) studies; and the Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes (GRADE) study comparing type 2 diabetes medications,” said Rodgers.

The landmark Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) clinical trial, which was the first study to show the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in people at high risk, was successfully completed and extended during her tenure. The DPP’s lifestyle change program became a model for diabetes prevention worldwide. It also serves as the foundation for the National Diabetes Prevention Program currently administered across the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Committed to translating advances from clinical research into clinical practice and to addressing disparities in health outcomes for people with diabetes, Fradkin created Diabetes Translation Research Centers and programs to advance pragmatic research in community and healthcare settings to foster innovative, interdisciplinary and cost-effective collaboration at research hospitals and institutions across the country. “An administrator with extraordinary vision, Judy also created or directed a diverse array of high-impact clinical and basic research programs, including several scientific consortia to define the genetic and environmental triggers of type 1 diabetes,” added Dr. Philip Smith, DEM deputy director and current acting director. “These studies include The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (the TEDDY study), an international study following children at risk of type 1 diabetes from birth to age 15.”

Recently, Fradkin launched an important series of diabetes initiatives to advance the development of artificial pancreas and other diabetes management technologies and to develop innovative strategies to protect or replace beta cells in diabetes. She also prioritized research on obesity, insulin action, and animal models of diabetes.

A major component of Fradkin’s leadership tenure at NIDDK is the Special Statutory Funding Program for Type 1 Diabetes Research. Commonly known as the Special Diabetes Program, this program was introduced through legislation in 1997.

Fradkin worked closely with bipartisan Congressional leaders, many institutes and centers at NIH and other DHHS agencies, and the broad diabetes research community to plan and implement an extraordinary series of initiatives over the last 22 years to deploy the nearly $3 billion in dedicated appropriations for type 1 diabetes research.

Committed to service, Fradkin led the Diabetes Mellitus Interagency Coordinating Committee, where she facilitated collaboration on diabetes among Federal entities. She also served on the Executive Committee of the National Diabetes Education Program, and she was a member of the Interagency Coordinating Committee on Human Growth Hormone and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. She also treated people who sought care at the Walter Reed National Naval Medical Center endocrinology clinic in Bethesda, Maryland.

Fradkin’s work was recognized with many awards during her time in government. She received the American Medical Association’s Dr. Nathan Davis Award for outstanding public service in the advancement of public health in 2003, the JDRF Hero Award in 2010, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Eugene T. Davidson, M.D., Award for Public Service in 2012, the JDRF David Rumbough Award for Scientific Excellence in 2015, and the C. Everett Koop Medal for Health Promotion and Awareness from the American Diabetes Association in 2018.

In retirement, Fradkin is enjoying the extra time to travel and spend with her new grandson. She is very proud of the exceptional staff she led in DEM. “I am grateful for the opportunity to work with talented friends and colleagues at NIDDK and in the broader research community,” she said. “It was an honor to help shape diabetes research. I look forward to continued progress to improve the lives of people with and at risk for diabetes.”

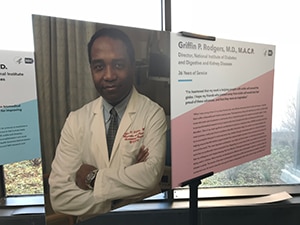

Rodgers honored in exhibit on African-American scientists

NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers was among 14 African-American scientists at NIH, plus four past NIHers, honored as part of an exhibition entitled, “Celebrating the Contributions of African-American Scientists Past and Present.” Presented as part of NIH’s Black History Month activities, the exhibition of photos and profiles ran through February in the National Library of Medicine.

Before the exhibition, Rodgers was asked to reflect on his own career achievements, both as leader of NIDDK and collaborator in the development of the first Food and Drug Administration-approved drug to treat sickle cell disease.

“Our mission is to improve health, and I try to accomplish that goal in some way every day, whether through conducting research on sickle cell disease or helping ensure that NIH dollars support studies that improve health outcomes in the community, the country, and around the world,” he said. “To me, that’s the most important contribution I can make and have made – conducting and supporting work that can profoundly improve people’s lives.” Read more about the exhibition in an NIH Record feature story.

NIDDK shines in 2018 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey results

By January W. PayneThe results of the 2018 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) are in and, once again, NIDDK ranks No. 1 across all large and medium institutes. Employee feedback indicated significant strengths across all categories, including employee engagement and global satisfaction.

This is extremely encouraging and a clear indicator of the effects that our continuous efforts have had on making NIDDK a great place to work,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers.

NIDDK uses survey results to gauge the perceptions of employees in key areas of their work experience that drive satisfaction and commitment, morale, productivity and capacity for the success of the Institute’s mission. Employee feedback is key in providing valuable insight into the Institute’s strengths and opportunities for improvement.

At NIDDK, the results are a springboard, not an endpoint. “Being good isn’t a reason to sit on your heels. We are always looking for ways to improve,” said NIDDK Executive Officer Camille Hoover. “Our employees are the underpinning of our organization, and it is critical that we continue to work to create and sustain an environment where all can flourish.”

To enable that growth, each year the NIDDK Executive Office uses the innovative EVS Analysis & Results Tool (EVS ART) to sort FEVS survey data into relevant, customizable metrics that enable staff to see their organization's strengths and opportunities for improvement. The tool, which originated at NIDDK, is currently being rolled out in many agencies and offices around the federal government. Read more about the tool’s development in the Spring 2018 NIDDK Director’s Update.

“We are determined to dig deeper into our Institute’s results and will continue to concentrate our efforts on improving across all levels,” Rodgers said. “With guidance from EVS ART, when our employees speak, we listen, and things happen.”

NIDDK website now faster with cellphone-friendly content

By Jen Rymaruk

NIDDK staff put on their virtual overalls and grabbed their pixel-wrenches to overhaul the main website—consisting of 3,650 pages of content used by more than 30 million people every year—to make it more intuitive and mobile-friendly.

“Upgrading such a large website took the proverbial village,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers. “But it was well worth it in added value. We are better able to serve our research community and the public by getting information into their hands in a faster, more intuitive manner.”

“We tightened up how information displays on phones, tablets, and desktops,” said Dana Sheets, NIDDK’s digital engagement lead. “We boosted our speed so that pages load faster. And we focused on making sure the content folks are searching for can be found.”

That focus is paying off: The website scored 83 on the latest results from the American Customer Satisfaction Index for the second half of 2018, above the industry standard of 75 out of 100 set for government websites. The website was also in the top three for mobile user satisfaction.

The upgrade started with our health information pages in 2017, using formatting for easier comprehension by people with low literacy levels. Health topics were also made available in the HHS Syndication Storefront—a site where other websites can pull and repost content from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services at no cost.

In early 2018, the About NIDDK and the News sections were updated to make plans and news about research advances easier to find, including NIDDK’s Strategic Plans and Reports, Funding Trends, and NIDDK’s Advisory and Coordinating committees.

To connect with those thinking about applying for a grant, the Current Funding Opportunities list was souped up to present all NIDDK funding opportunities to the community in a single searchable, filterable table. The Human Subjects Research page is also regularly updated.

Become a Reviewer was added to ease self-nomination for anyone interested in participating in review of NIDDK grant applications. According to Dr. Karl Malik, director of NIDDK’s Division of Extramural Activities, reviewing grant applications is a fantastic way to learn more about what makes a successful application.

The finishing touch was an improved Research at NIDDK section launched in December 2018 to showcase the Intramural Research Program. The new design highlights the science and helps labs showcase their staff and fellows to attract the brightest future contributors to NIDDK research.

NIDDK’s Dr. Anne Sumner speaks at Rwanda symposium

Dr. Anne E. Sumner, chief of the Section on Ethnicity and Health in the NIDDK Diabetes, Endocrinology and Obesity Branch, recently presented at the inaugural University of Global Health Equity Symposium in Rwanda on how early life nutritional exposures impact the rate of diabetes in adulthood. Sumner worked with partners at the NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the Government of Rwanda’s Ministry of Health establish the NIH NIMHD-NIDDK-Rwandan Health Program in 2016. She was joined at the symposium by her NIH colleague Dr. Roger Glass, director of the Fogarty International Center.

Getting to know: Winnie Martinez

Winnie Martinez is a program director in the NIDDK Office of Minority Health Research Coordination (OMHRC), which provides opportunities for undergraduate students and researchers from underrepresented backgrounds. Martinez manages the Network of Minority Health Research Investigators and the NIDDK Diversity Summer Research Training Program. She spoke with Lisa Yuan about her 30-plus years at NIH, why she loves her work, and what advice she gives to young and future investigators.

What brought you to NIH?I was a business major in college with plans of opening my own business, when a friend told me to apply for a job at the NIH. I started as a grants technical assistant in what was then the Division of Research Grants. A position opened up at NIDDK and I eventually worked in the Office of Scientific Program and Policy Analysis, which was a wonderful experience. That is where I first connected with Dr. Larry Agodoa. We ended up working together on the very first health disparities strategic plan, and in 2001, the OMHRC was established.

Can you share more about your everyday work?I manage the Network of Minority Health Research Investigators (NMRI) and the Diversity Summer Research Training Program (DSRTP). I also do a lot of outreach to promote OMHRC’s programs. And I’m constantly communicating with people – from students and young investigators to senior investigators and heads of medical centers. Through the NMRI, I’ve been able to develop one-on-one relationships with so many amazing people across the nation. We all share the common goal of helping future researchers and doctors – students who might not necessarily have had the opportunities or connections that we are able to provide them.

What do you enjoy most about your work?What I enjoy and am most proud of is being able to help people and provide them with resources. When I get messages from people telling me how much our programs helped them, how I made a difference in their lives, or how they would not be where they are now if it weren’t for DSRTP or NMRI, it is so rewarding. One of the greatest things about my job is the opportunity to connect people. If someone is struggling in an area, such as writing a grant or looking for someone to collaborate with, I have a spectrum of people I can call who can help or provide mentorship.

What do you hope to see the OMHRC accomplish in the next decade?The NMRI began with about 30 members, and it’s now 600+. So we’re doing a great job. But I hope we can expand on our programs, reach out to more students, and continue to provide resources to young investigators. So many of these students have a story behind them; they’ve had struggles in life, and still they push on. That’s what makes me push for these programs. Our students come from underrepresented communities – Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, etc. – and may not have role models to guide them in their careers. Some dream of being doctors, but are scared to leave their villages or reservations. We give them guidance and comfort, so that when they come here, they know they have a support system.

What advice do you give young scientists from underrepresented backgrounds trying to enter the field?I tell them, never give up. There will be challenges, but also many people to support you. It’s essential to find good mentors in any area of life. Choose mentors you admire, and know that what they have achieved is reachable because they too have faced struggles to get where they are. And finally, stay open-minded. Sometimes an opportunity presents itself that may not feel like the right path. But it could open the door to something you never considered. Many students come here thinking they want to be primary doctors and discover a love for the lab and research. The opportunities we provide for young people are often life-changing events for them. This is why I do what I do. It’s just wonderful.