Renal Tubular Acidosis

On this page:

- What is renal tubular acidosis?

- How common is RTA?

- Who is more likely to have RTA?

- What are the complications of RTA?

- What are the signs and symptoms of RTA?

- What are the causes of RTA?

- How do health care professionals diagnose RTA?

- How do health care professionals treat RTA?

- How can I prevent RTA?

- How does eating, diet, and nutrition affect RTA?

- Clinical Trials for Renal Tubular Acidosis

What is renal tubular acidosis?

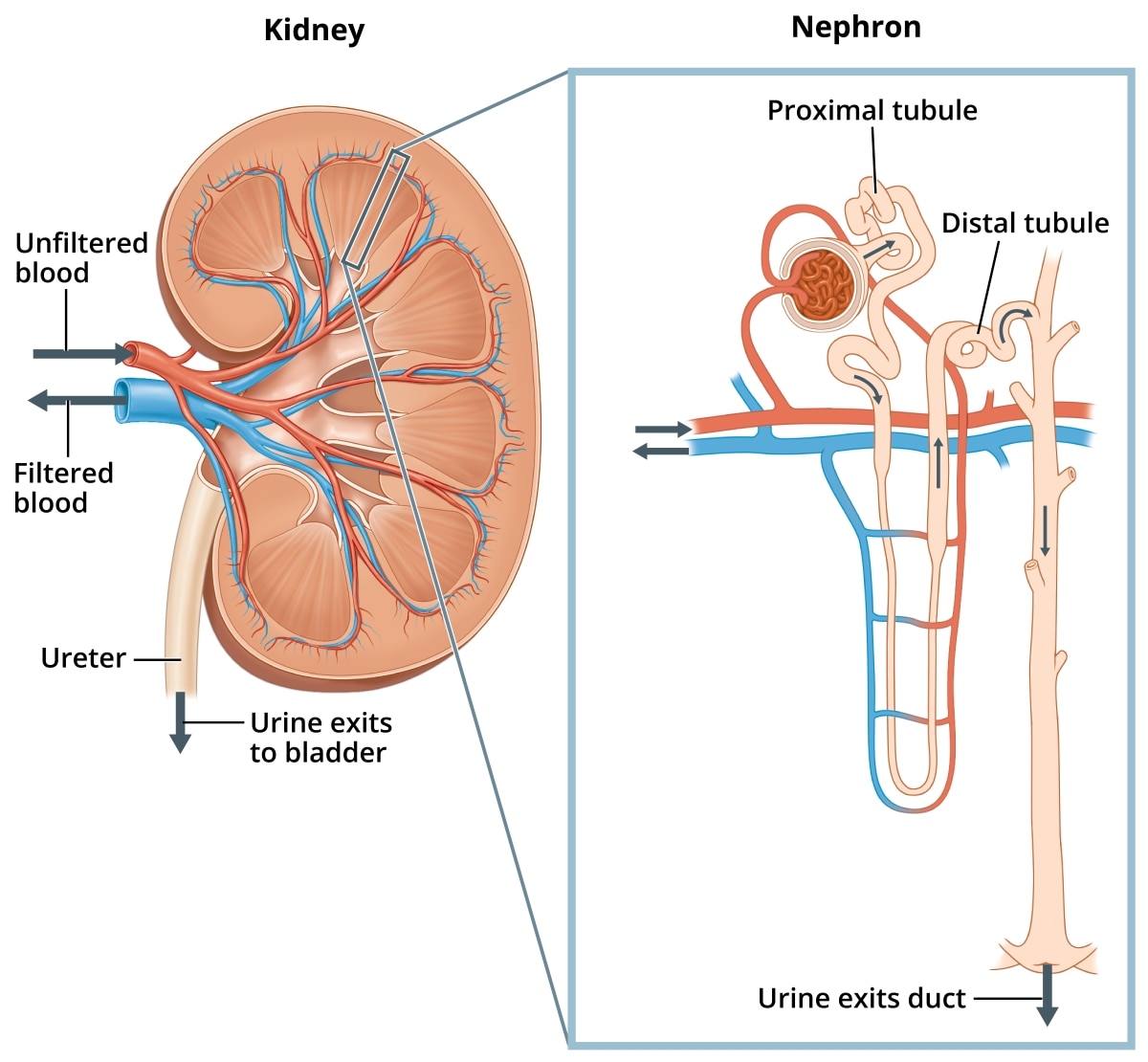

Renal tubular acidosis (RTA) occurs when the kidneys do not remove acids from the blood into the urine as they should. The acid level in the blood then becomes too high, a condition called acidosis. Some acid in the blood is normal, but too much acid can disturb many bodily functions.

There are three main types of RTA.

- Type 1 RTA, or distal RTA, occurs when there is a problem at the end or distal part of the tubules.

- Type 2 RTA, or proximal RTA, occurs when there is a problem in the beginning or proximal part of the tubules.

- Type 4 RTA, or hyperkalemic RTA, occurs when the tubules are unable to remove enough potassium, which also interferes with the kidney’s ability to remove acid from the blood.

Type 3 RTA is rarely used as a classification now because it is thought to be a combination of type 1 and type 2 RTA.

Structures in the kidney called nephrons filter your blood and remove wastes, such as acids, which go to your bladder and leave the body in your urine.

Structures in the kidney called nephrons filter your blood and remove wastes, such as acids, which go to your bladder and leave the body in your urine.How common is RTA?

RTA is a rare disease that is often misdiagnosed or undiagnosed,1 making it difficult to determine the true frequency in the general population.2

Who is more likely to have RTA?

You are more likely to have type 1 RTA if you inherit specific genes from your parents or if you have certain autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome or lupus.2

If you have Fanconi syndrome or are taking medicines to treat HIV or viral hepatitis, you are more likely to have type 2 RTA.1 People who inherit genes for type 2 RTA from their parents may also have it. In adults, type 2 RTA can be a complication or side effect of multiple myeloma,3 exposure to toxins, or certain medications. In rare cases, type 2 RTA occurs in people who experience chronic rejection of a transplanted kidney.4

If you have low levels of the hormone aldosterone, cannot urinate freely because of an obstruction, or had a kidney transplant, you are more likely to develop type 4 RTA.1 One in five people develop type 4 RTA if they experience rejection of a transplanted kidney or are taking immunosuppressive medications.1

What are the complications of RTA?

Type 1 RTA

Untreated type 1 RTA causes children to grow more slowly and adults to develop progressive kidney disease and bone diseases. Adults and children with untreated type 1 RTA may develop kidney stones because of abnormal calcium deposits that build up in the kidneys. These deposits prevent the kidneys from working properly.

Other diseases and conditions related to type 1 RTA include

- a hereditary form of deafness

- renal medullary cystic disease

- sickle cell anemia

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- urinary tract infections

Type 2 RTA

Untreated type 2 RTA may cause children to grow more slowly. In addition, type 2 RTA may cause rickets5—a bone disease—and dental disease in both children and adults.6 A very low potassium level can develop during treatment of type 2 RTA with alkali.4

Type 4 RTA

In people with type 4 RTA, high levels of potassium in the blood can lead to muscle weakness7 or heart problems, such as slow or irregular heartbeats and cardiac arrest.8

What are the signs and symptoms of RTA?

The major signs of type 1 RTA and type 2 RTA are low levels of potassium and bicarbonate—a waste product produced by your body—in the blood. The potassium level drops if your kidneys send too much potassium into your urine instead of returning it to the blood.

Because potassium helps regulate your nerve and muscle health and heart rate, low potassium levels can cause

- extreme weakness

- irregular heartbeat

- paralysis

- death

The major signs of type 4 RTA are high potassium and low bicarbonate levels in the blood. Symptoms of type 4 RTA include9

- abdominal pain

- fatigue that does not go away

- weak muscles

- not feeling hungry

- weight change

What are the causes of RTA?

Type 1 RTA

Type 1 RTA may be inherited. Researchers have identified at least three different genes that may cause the inherited form of the disease.2 People with sickle cell anemia or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which are also inherited, may develop type 1 RTA later in life.

However, type 1 RTA may develop because of an autoimmune disease, such as Sjögren's syndrome or lupus, that can affect many parts of the body. These diseases may interfere with the removal of acid from your blood.

Type 1 RTA can also be caused by certain medications, including some used for pain and bipolar disorder, conditions causing high calcium in the urine, blocked urinary tract, or rejection of a transplanted kidney.

Type 2 RTA

Type 2 RTA may be inherited or caused by other inherited conditions such as

- cystinosis, a rare disease in which cystine crystals are deposited in bones and other tissues

- hereditary fructose intolerance

- Wilson disease

Type 2 RTA can also be caused by acute lead poisoning or chronic exposure to cadmium. It can also occur in people treated with certain medications used in chemotherapy and to treat HIV, viral hepatitis, glaucoma, migraines, and seizures.

Type 2 RTA almost always occurs as part of Fanconi syndrome. The main features of Fanconi syndrome include

- abnormal excretion of glucose, amino acids, citrate, bicarbonate, and phosphate into the urine

- low blood potassium levels

- low levels of vitamin D

Type 4 RTA

Type 4 RTA can occur when blood levels of the hormone aldosterone are low or when the kidneys do not respond to the hormone. Aldosterone directs the kidneys to regulate the level of sodium, which also affects the levels of chloride and potassium, in the blood.

Certain medicines that interfere with the kidney’s task of moving electrolytes between your blood and urine may also cause type 4 RTA. Some of these include

- blood pressure medicines called angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- certain diuretics used to treat congestive heart failure that do not decrease potassium in the blood

- certain medicines to prevent blood from clotting

- some immunosuppressive medicines that prevent the rejection of transplanted organs

- painkillers called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- antibiotics used to treat pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and traveler’s diarrhea

Type 4 RTA can also occur when diseases or an inherited disorder affect how the kidneys work, such as

- Addison's disease, due to disease or removal of the adrenal glands

- congenital adrenal insufficiency

- aldosterone synthase deficiency

- Gordon syndrome

- amyloidosis

- diabetic kidney disease

- HIV/AIDS

- kidney transplant rejection

- lupus

- sickle cell disease

- urinary tract obstruction

How do health care professionals diagnose RTA?

Your health care professional will review your medical history and order blood and urine tests to measure the levels of acid, base, and potassium in your blood and urine. If your blood is more acidic than it should be and your urine is less acidic than it should be, RTA may be the reason, but a health care professional will need to rule out other causes.

If you are diagnosed with RTA, information about the sodium, potassium, and chloride levels in your urine and the potassium level in your blood will help identify which type of RTA you have.

How do health care professionals treat RTA?

For all types of RTA, drinking a solution of sodium bicarbonate or sodium citrate will lower the acid level in your blood. This alkali therapy can prevent kidney stones from forming and make your kidneys work more normally so kidney failure does not get worse.

Infants with type 1 RTA may need potassium supplements, but older children and adults rarely do because alkali therapy prevents the kidneys from excreting potassium into the urine.

Children with type 2 RTA will also drink an alkali solution (sodium bicarbonate or potassium citrate) to lower the acid level in their blood, prevent bone disorders and kidney stones, and grow normally. Some adults with type 2 RTA may need to take vitamin D supplements to help prevent bone problems.

People with type 4 RTA may need other medicines to lower the potassium levels in their blood.

If your RTA is caused by another condition, your health care professional will try to identify and treat it.

How can I prevent RTA?

Inherited types of RTA cannot be prevented,10 and most of the disorders that cause RTA are not preventable.

How does eating, diet, and nutrition affect RTA?

Researchers don’t yet know whether a diet low in acidic foods can have a positive effect on RTA.

Clinical Trials for Renal Tubular Acidosis

The NIDDK conducts and supports clinical trials in many diseases and conditions, including kidney diseases. The trials look to find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease and improve quality of life.

What are clinical trials for RTA?

Clinical trials—and other types of clinical studies—are part of medical research and involve people like you. When you volunteer to take part in a clinical study, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future.

Researchers are studying many aspects of RTA, such as

- new drug treatments

- the role of different genes in the development of RTA

Find out if clinical studies are right for you.

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical studies for RTA are looking for participants?

You can find clinical studies on RTA at ClinicalTrials.gov. In addition to searching for federally funded studies, you can expand or narrow your search to include clinical studies from industry, universities, and individuals; however, the National Institutes of Health does not review these studies and cannot ensure they are safe. Always talk with your health care provider before you participate in a clinical study.

References

[1] Mustaqeem R, Arif A. Renal tubular acidosis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; January 2019. Updated January 17, 2019. Accessed November 30, 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519044/

[2] National Organization for Rare Diseases: Rare Diseases Database. Primary distal renal tubular acidosis. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/primary-distal-renal-tubular-acidosis/

[3] Kashoor I, Batlle D. Proximal renal tubular acidosis with and without Fanconi syndrome. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice. 2019;38(3):267–281. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.19.056

[4] Haque SK, Ariceta G, Batlle D. Proximal renal tubular acidosis: a not so rare disorder of multiple etiologies. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2012;27(12):4273–4287. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfs493

[5] Chanchlani R, Nemer P, Sinha R, et al. An overview of rickets in children. Kidney International Reports. 2020;5(7):980–990. Published April 11, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2020.03.025

[6] Lacruz RS, Habelitz S, Wright JT, Paine ML. Dental enamel formation and implications for oral health and disease. Physiological Reviews. 2017;97(3):939–993. doi:10.1152/physrev.00030.2016

[7] Menegussi J, Tatagiba LS, Vianna JGP, Seguro AC, Luchi WM. A physiology-based approach to a patient with hyperkalemic renal tubular acidosis. Jornal Brasileiro de Nefrologia. 2018;40(4):410–417. doi:10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-3821

[8] Montford JR, Linas S. How dangerous is hyperkalemia? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017;28:3155–3165. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016121344

[9] Adrenal insufficiency & Addison’s disease. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Accessed November 30, 2020. www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/adrenal-insufficiency-addisons-disease

[10] Watanabe T. Improving outcomes for patients with distal renal tubular acidosis: recent advances and challenges ahead. Pediatric Health, Medicine, and Therapeutics. 2018;9:181–190. doi:10.2147/PHMT.S174459

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Thomas D. DuBose, M.D., M.A.C.P., Professor of Medicine Emeritus, Wake Forest Baptist Health, and Richard H. Sterns, M.D., Professor Emeritus, University of Rochester Medical Center