Acquired Cystic Kidney Disease

On this page:

- What is acquired cystic kidney disease?

- What are the differences between acquired cystic kidney disease and polycystic kidney disease?

- How common is acquired cystic kidney disease?

- What causes acquired cystic kidney disease?

- What are the signs and symptoms of acquired cystic kidney disease?

- What are the complications of acquired cystic kidney disease?

- How is acquired cystic kidney disease diagnosed?

- How is acquired cystic kidney disease treated?

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

- Clinical Trials

What is acquired cystic kidney disease?

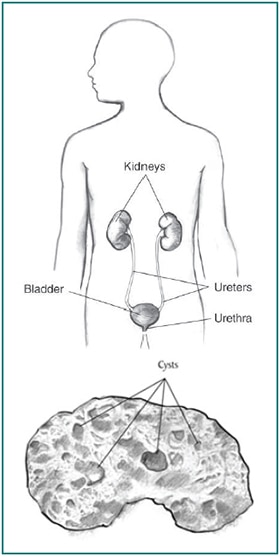

Acquired cystic kidney disease happens when a person's kidneys develop fluid-filled sacs, called cysts, over time. Acquired cystic kidney disease is not the same as polycystic kidney disease (PKD), another disease that causes the kidneys to develop multiple cysts.

Acquired cystic kidney disease occurs in children and adults who have

- chronic kidney disease (CKD)—a condition that develops over many years and may lead to end-stage kidney disease, or ESRD. The kidneys of people with CKD gradually lose their ability to filter wastes, extra salt, and fluid from the blood properly.

- end-stage kidney disease—total and permanent kidney failure that requires a kidney transplant or blood-filtering treatments called dialysis.

The cysts are more likely to develop in people who are on kidney dialysis. The chance of developing acquired cystic kidney disease increases with the number of years a person is on dialysis. However, the cysts are caused by CKD or kidney failure, not dialysis treatments.

What are the differences between acquired cystic kidney disease and polycystic kidney disease?

Acquired cystic kidney disease differs from PKD in several ways. Unlike acquired cystic kidney disease, PKD is a genetic, or inherited, disorder that can cause complications such as high blood pressure and problems with blood vessels in the brain and heart.

The following chart lists the differences:

People with Polycystic Kidney Disease

- are born with a gene that causes the disease

- have enlarged kidneys

- develop cysts in the liver and other parts of the body

People with Acquired Cystic Kidney Disease

- do not have a disease-causing gene

- have kidneys that are normal-sized or smaller

- do not form cysts in other parts of the body

In addition, for people with PKD, the presence of cysts marks the onset of their disease, while people with acquired cystic kidney disease already have CKD when they develop cysts.

How common is acquired cystic kidney disease?

Acquired cystic kidney disease becomes more common the longer a person has CKD.

- About 7 to 22 percent of people with CKD already have acquired cystic kidney disease before starting dialysis treatments.

- Almost 60 percent of people on dialysis for 2 to 4 years develop acquired cystic kidney disease.1

- About 90 percent of people on dialysis for 8 years develop acquired cystic kidney disease.1

What causes acquired cystic kidney disease?

Researchers do not fully understand what causes cysts to grow in the kidneys of people with CKD. The fact that these cysts occur only in the kidneys and not in other parts of the body, as in PKD, indicates that the processes that lead to cyst formation take place primarily inside the kidneys.2

What are the signs and symptoms of acquired cystic kidney disease?

A person with acquired cystic kidney disease often has no symptoms. However, the complications of acquired cystic kidney disease can have signs and symptoms.

What are the complications of acquired cystic kidney disease?

People with acquired cystic kidney disease may develop the following complications:

- an infected cyst, which can cause fever and back pain.

- blood in the urine, which can signal that a cyst in the kidney is bleeding.

- tumors in the kidneys. People with acquired cystic kidney disease are more likely than people in the general population to have cancerous kidney tumors. However, the chance of cancer spreading is lower in people with acquired cystic kidney disease than that of other kidney cancers not associated with acquired cystic kidney disease, and the long-term outlook is better.1

How is acquired cystic kidney disease diagnosed?

A health care provider may diagnose a person with acquired cystic kidney disease based on

- medical history

- imaging tests

Medical History

Taking a medical history may help a health care provider diagnose acquired cystic kidney disease. A health care provider may suspect acquired cystic kidney disease if a person who has been on dialysis for several years develops symptoms such as fever, back pain, or blood in the urine.

Imaging Tests

To confirm the diagnosis, the health care provider may order one or more imaging tests. A radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images from these tests, and the patient does not need anesthesia.

- Ultrasound uses a device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create an image of their structure. A specially trained technician performs the procedure in a health care provider's office, an outpatient center, or a hospital. The images can show cysts in the kidneys as well as the kidneys' size and shape.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scans use a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images. For a CT scan, a nurse or technician may give the patient a solution to drink and an injection of a special dye, called contrast medium. CT scans require the patient to lie on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device where an x-ray technician takes the x-rays. An x-ray technician performs the procedure in an outpatient center or a hospital. CT scans can show cysts and tumors in the kidneys.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a test that takes pictures of the body's internal organs and soft tissues without using x-rays. A specially trained technician performs the procedure in an outpatient center or a hospital. Although the patient does not need anesthesia, a health care provider may give people with a fear of confined spaces light sedation, taken by mouth. An MRI may include the injection of contrast medium. With most MRI machines, the patient will lie on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device that may be open-ended or closed at one end. Some machines allow the patient to lie in a more open space. During an MRI, the patient, although usually awake, must remain perfectly still while the technician takes the images, which usually takes only a few minutes. The technician will take a sequence of images from different angles to create a detailed picture of the kidneys. During the test, the patient will hear loud mechanical knocking and humming noises from the machine.

Sometimes a health care provider may discover acquired cystic kidney disease during an imaging exam for another condition. Images of the kidneys may help the health care provider distinguish acquired cystic kidney disease from PKD.

How is acquired cystic kidney disease treated?

If acquired cystic kidney disease is not causing complications, a person does not need treatment. A health care provider will treat infections with antibiotics—medications that kill bacteria. If large cysts are causing pain, a health care provider may drain the cyst using a long needle inserted into the cyst through the skin.

When a surgeon transplants a new kidney into a patient's body to treat kidney failure, acquired cystic kidney disease in the damaged kidneys, which usually remain in place after a transplant, often disappears.

A surgeon may perform an operation to remove tumors or suspected tumors. In rare cases, a surgeon performs an operation to stop cysts from bleeding.

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

No specific diet will prevent or delay acquired cystic kidney disease. In general, a diet designed for people on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis reduces the amount of wastes that accumulate in the body between dialysis sessions.

More information is provided in the NIDDK health topics, Eating & Nutrition for Hemodialysis and Diet & Nutrition for Adults with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease.

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

(NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Catherine Kelleher, M.D., University of Colorado Health Sciences Center