News Around NIDDK

In NIDDK labs, it IS easy being green!

NIDDK focuses on environmental sustainability

By Katie Clark

At NIDDK, lab by lab, even small changes are making a big impact in environmental sustainability in the scientific workplace. In NIH-certified Green Labs in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), changes prompted by a desire to improve the environment and human health have ended up saving energy, space, and even money in the process.

In one “green” example, the Genetics and Metabolism Section of NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Branch traded in traditional X-ray imaging for digital imaging systems, eliminating the need for costly X-ray films and hazardous waste, and freeing up laboratory space previously used for dark rooms and film equipment. This change led to a savings of more than $11,000 in one year alone. This green equipment uses less space and offsets waste.

This green equipment uses less space and offsets waste.

“Improving environmental practices in the lab doesn’t require drastic changes,” said Minoo Shakoury-Elizeh, an NIH Green Lab Champion and technical lab manager in NIDDK. “Small changes add up, leading to improved conservation of energy and water, less waste, and safer, more effective lab practices.”

NIDDK has been at the forefront of the NIH’s green lab movement. Its Genetics and Metabolism Section is where iron and its role in diseases within NIDDK’s mission are studied. It’s also where Shakoury-Elizeh championed sustainability efforts as one of NIDDK’s four NIH-certified Green Labs, following practices like replacing wet blotting instruments used to detect proteins with safer dry blotting versions, eliminating toxic methanol waste. An additional perk – the dry machine can detect proteins four times faster than wet blotting methods.

Although there is often an upfront cost with purchasing new equipment, long-term benefits like reduced energy, time, maintenance and associated costs, can be substantial. To help offset costs of new equipment, Shakoury-Elizeh suggests sharing equipment with another lab or office.

Although there is often an upfront cost with purchasing new equipment, long-term benefits like reduced energy, time, maintenance and associated costs, can be substantial. To help offset costs of new equipment, Shakoury-Elizeh suggests sharing equipment with another lab or office.

The NIH Green Labs Program was developed in 2018 to increase awareness and participation in sustainable practices without sacrificing research. Shakoury-Elizeh and colleagues across NIH have since worked to implement and expand NIH’s sustainability efforts.

“Minoo is one of the pioneers who started the NIH Green Labs movement to educate researchers and promote the use of safer lab products,” said Bani Bhattacharya, NIH Green Labs program manager. “It is remarkable to see how her passion and dedication has grown over the years in increasing awareness and communicating sustainability efforts across the NIH.”

Minoo Shakoury-Elizeh in NIH-certified Green Lab, the Genetics and Metabolism Section of NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Brach.

Minoo Shakoury-Elizeh in NIH-certified Green Lab, the Genetics and Metabolism Section of NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Brach.In one effort, Shakoury-Elizeh and Dr. Daman Kumari, staff scientist in NIDDK’s Laboratory of Cell and Molecular Biology, expanded NIH’s Styrofoam Take-Back program where Styrofoam shipping containers are returned for reuse, resulting in a reduction of solid waste. Between 2010 and 2021, the quantity of NIH-recycled Styrofoam coolers diverted from landfill disposal increased 27-fold – from 513 pounds to 13,900 pounds.

Shakoury-Elizeh and Kumari, among others, were recognized as Change Agents in the 2019 Department of Health and Human Services Green Champion Awards for leading sustainability by example at the NIH. This group serves as the voice of the NIH scientific community to senior-level management and have been intimately involved with green efforts within their own teams and the NIH Sustainable Lab Practices Working Group. Because of their efforts, for example, ethidium bromide, a toxic chemical dye used to detect DNA and RNA, was replaced with a nontoxic alternative in many labs across the NIH.

“In line with our mission to improve health and quality of life for all, NIDDK is committed to conserving resources and reducing our environmental footprint,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers. “Making sustainability practices a priority is important for every organization and is part of our responsibility to the communities we serve.”

Shakoury-Elizeh concurs. “Going green is a win for everyone, for our research, and for our planet – and it doesn’t have to be hard,” she said. “From purchasing energy-efficient equipment, to swapping out toxic chemicals, to placing ‘turn off’ stickers on light switches, once you start looking, there are paths to a greener lab everywhere.”

How can you go green? To learn more about the Green Labs Program or application process, visit the NIH Green Labs Program website.

ICYMI: NIDDK releases new strategic plan

Launched in December, NIDDK’s Strategic Plan for Research presents a broad vision for accelerating research over the next five years to improve people’s health and quality of life. The plan’s scientific goals will guide NIDDK to build on its 70+ years of discovery, progress, and innovation.

Launched in December, NIDDK’s Strategic Plan for Research presents a broad vision for accelerating research over the next five years to improve people’s health and quality of life. The plan’s scientific goals will guide NIDDK to build on its 70+ years of discovery, progress, and innovation.

Several cross-cutting topics are addressed throughout the plan, including reducing health disparities and increasing health equity, improving women’s health, and strengthening biomedical research workforce diversity. The plan also addresses the importance of serving as an efficient and effective steward of public resources. As highlighted throughout the plan, NIDDK is committed to empowering a multidisciplinary research community, engaging diverse stakeholders, and improving pathways to health for all through prevention, treatment, and health equity.

The Strategic Plan was developed with extensive input from researchers, people living with the diseases in NIDDK’s mission, NIDDK staff, and the public. It is now available on the NIDDK website.

Editors' note: Want to hear more? NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers and his colleagues Drs. Pamela Thornton and Katrina Serrano will be live on Facebook Monday, April 25, at 1:00 pm ET for a segment titled “Improving Health through Diversity, Equity and Opportunity: NIDDK’s Strategic Plan in Action” to discuss NIDDK’s goals to increase health equity and strengthen the diversity of the scientific workforce.

NIDDK Fellow Spotlight

Name: Agnes Karasik, Ph.D.

Name: Agnes Karasik, Ph.D.

Hometown: Budapest, Hungary

Current position: Postdoctoral fellow, Section on mRNA Regulation and Translation, Laboratory of Biochemistry and Genetics

What inspired you to pursue a research career?

From a very young age I was fascinated with how animals and plants function. At 14, I heard about genes and proteins and was so astonished that I decided to be a molecular biologist. I spent hours in the library reading about science and the lives and achievements of past scientists. Women role models, like Marie Curie and Jane Goodall, had a great impact on me and inspired me to pursue a research career.

While I had a clear vision, the path was not always smooth. I was the first in my family to go to college, and my relatives could not provide support for navigating academic life. When I first joined a research lab as an undergraduate in Hungary, I felt that I didn’t belong. It also struck me that while most graduate students and postdocs were female at my institute, very few succeeded beyond that level. When I started my doctoral research in the United States, I was fortunate to have a supportive mentor and a nurturing environment that enabled me to succeed as a scientist.

Due to my experiences, I feel responsible to create a more inclusive and welcoming environment in the biomedical sciences through mentoring, advocating for changes that remove barriers for women and underserved groups, and organizing events that highlight outstanding - but overlooked - scientists.

What public health problem do you ultimately hope to solve with your research?

My passion towards molecular biology has persisted, and I’ve been fortunate to work on several molecular mechanisms in the cell related to human diseases. Currently, my research is focusing on an antiviral host factor, RNase L. This antiviral factor plays an important role in clearing viral infections including West Nile virus and SARS-CoV2. However, molecular details of how this antiviral factor works are still mostly unclear. Understanding RNase L-related antiviral mechanisms could enhance both our knowledge of viral infections and facilitate the development of antiviral therapeutics.

Join us for a Facebook LIVE event

Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers and his colleagues Dr. Susan Yanovski and Dr. Marc Reitman will be live on Facebook Monday, March 21, at 1:00 pm ET for a segment titled “Obesity Research, What’s Next? Current and emerging research.” They will discuss NIDDK’s current and emerging research initiatives to help prevent and treat obesity.

Getting to Know: Dr. Caroline Philpott

Dr. Caroline Philpott is the chief of the Genetics and Metabolism Section in NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Branch. She leads a team that studies how iron is used in the body, including novel ways it can be utilized to target diseases in NIDDK’s mission. She sat down virtually with Katie Clark to talk about her work at NIDDK, her hopes for the future of her field, her passions in and outside of NIH, and much more.

Dr. Caroline Philpott is the chief of the Genetics and Metabolism Section in NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Branch. She leads a team that studies how iron is used in the body, including novel ways it can be utilized to target diseases in NIDDK’s mission. She sat down virtually with Katie Clark to talk about her work at NIDDK, her hopes for the future of her field, her passions in and outside of NIH, and much more.

You specialize in researching the genetics and cell biology of iron absorption and use – what led you to this field and to the NIH?

I came to NIH as a medical student in 1985 in the first class of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute-NIH Research Scholars Program, working in NIDDK’s Laboratory of Cellular and Developmental Biology. I loved it. When I was planning for after my residency, it seemed that no one was having as much fun as I’d had when I was a bench researcher at NIH, so I came back to NIH as a postdoc to study iron.

In 1998, I became a principal investigator in NIDDK’s Liver Diseases Branch to continue my research of iron in cells. This area is critically important because how cells use metals like iron is understudied. My initial research used baker’s yeast as a model for iron balance. My hopes to translate those results to animal models was risky and might not have worked. I am thankful NIH supported the research because as it turned out, it worked, and I was able to quickly expand my research into animal models.

What are your hopes for the future of your field?

I hope that our continued research will reveal the importance of the management system for iron in cells and tissues in the human body. Essentially, we need to get iron, an essential nutrient, where it needs to go in the body, and harness its potential for therapeutic use. We aim to better understand the body’s regulatory systems that allow us to use iron safely and efficiently, including a new process called ferroptosis which is a type of programmed cell death dependent on iron. The discovery of ferroptosis has prompted research in the hopes of developing agents that can harness such activity to potentially battle cancer or infection.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

Working with other scientists, trainees, and fellows is really fun, especially at the bench when the data comes together. And I really love teaching the process of discovery to others.

Your lab is an NIH-certified Green Lab. Can you tell me more about that and why sustainability is important to you?

I credit Minoo Shakoury-Elizeh, a former biologist in my lab, for taking initiative in making our lab green. She went above and beyond her role, interacting with lab managers from across NIH, and finding the NIH Green Labs program. It is clear to all of us in the lab that to be responsible stewards of the environment, we need to reduce our lab’s impact, and there’s lots of easy ways to do that. The changes we made in our lab helped reduce and recycle waste, use less harmful chemicals, and save energy and space. Editors’ Note: For more on NIDDK Green Labs, see In NIDDK labs, it IS easy being green!.

What advice do you have for people beginning their research career?

There are so many opportunities in the realm of science and research – if you find an activity you love, you should find a place where you can do just that. Some people, like me, fall in love with researching at the bench. Others are passionate about grants administration or science communication, or one of the many science careers out there. It may not be the same thing your mentor loves and that’s okay. If you aren’t having fun, reassess if you are in the right place. A great career path, with lots of room for growth, will keep you intellectually stimulated forever.

What are your interests outside of NIH?

Anyone who knows me well knows I’m a crazy bicyclist, which is what I do for fun outside of work. I’m one of those people who commute to NIH on a bike every day. My husband and I like to visit other countries and parts of the world to tour them on bikes, and we hope one day soon we can pick that back up.

Dr. Caroline Philpott bikes in Corsica.

Dr. Caroline Philpott bikes in Corsica. Collaboration with USDA sprouts new dietary biomarker centers

What’s the effect of an apple a day? Is that effect the same for everyone? A new NIDDK collaboration with the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) begins an endeavor moving us closer to answering these complex questions posed in the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research. Bringing together large multidisciplinary teams and establishing three new research centers, the goal of the Dietary Biomarker Development Consortium (DBDC) is to first detect the signals in the body that confirms someone ate an apple.

“A dietary biomarker is a molecule or compound in the urine or blood that acts like a signpost, telling us what someone ate in the last day or eats regularly,” said Dr. Padma Maruvada, program director for nutrient metabolism in the NIDDK Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition. “With clear biological signposts, dietary research is more precise and paves the way for knowing the association between what we eat and how it impacts health.”

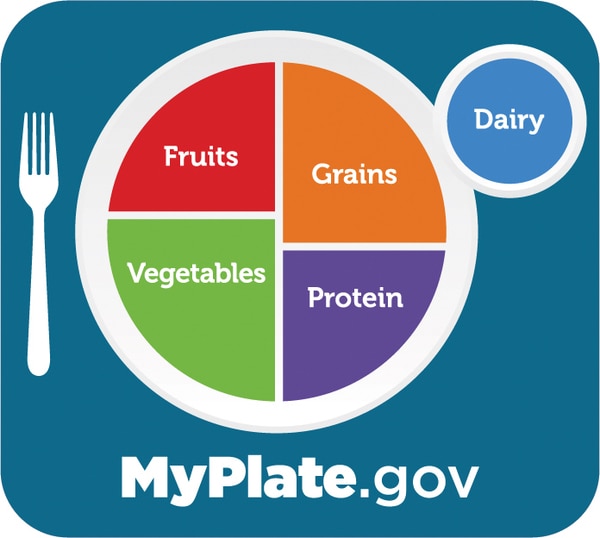

DBDC will use the USDA MyPlate as a guide for selecting foods to investigate, and each center will focus on a major food group. Centers at Harvard University, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, and University of California, Davis will begin recruiting volunteers to participate in controlled feeding studies and other clinical studies this summer.

DBDC will use the USDA MyPlate as a guide for selecting foods to investigate, and each center will focus on a major food group. Centers at Harvard University, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, and University of California, Davis will begin recruiting volunteers to participate in controlled feeding studies and other clinical studies this summer.

Drs. Lisa Jahns and Lydia Kaume, national program leaders for USDA-NIFA expressed how this program can enhance nutrition research. “A limitation in current dietary intervention studies is that there are few objective measures of dietary intake,” they said. “The dietary biomarker development centers will use state-of-the-art analytical and statistical tools to find biomarkers of various foods such as fruits."

The seed for the collaboration was planted in 2018, when nutrition researchers from across the U.S., Canada, and Europe gathered at a workshop in Bethesda, MD, and identified a need to identify dietary biomarkers and add them to an accessible database using a standardized approach.

Conventional nutrition research often relies on self-reported surveys or costly inpatient studies. The new program could provide a better alternative, Maruvada said. “Thanks to this new collaboration, we can strengthen nutrition research by supporting the growth of a large database of shared, standardized, and verified biomarkers – which could in turn help us better determine the effectiveness of dietary interventions and adapt them to the individual.”

To validate biomarkers, researchers need to identify the chemical compounds in food and the way these compounds are biologically transformed in the body. Most raw foods contain over 10,000 possible biomarkers and can be influenced by genetics, food environments, and cultural or lifestyle factors. It’s a huge challenge and, thus far, fewer than 1,000 food-derived compounds have been studied and documented in research databases .

“The dietary biomarkers program has the opportunity to make great progress in achieving the goals of the NIH Strategic Plan for Nutrition Research,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers. “With this NIDDK and NIFA collaboration, we’re building on each other’s strengths to advance precision medicine for nutrition – so we can truly understand what people eat and the effect of that ‘apple a day.’”

To learn more about participating in clinical research visit the NIDDK Clinical Trials webpage.