News Around NIDDK

Marking 50 years of the Diabetes Research Centers Program

By Alyssa Voss

Drs. Consuelo H. Wilkins, Senior Vice President and Senior Associate Dean for Health Equity and Inclusive Excellence at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Griffin Rodgers, NIDDK director, and Alvin C. Powers, director of the Vanderbilt DRTC, stand together at the Annual Diabetes Day symposium. Credit: Susan Urmy

Drs. Consuelo H. Wilkins, Senior Vice President and Senior Associate Dean for Health Equity and Inclusive Excellence at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Griffin Rodgers, NIDDK director, and Alvin C. Powers, director of the Vanderbilt DRTC, stand together at the Annual Diabetes Day symposium. Credit: Susan UrmyWhat is the best way to find a cure for diabetes? In the 1970s, prominent endocrinologist Dr. Robert Williams, former chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington, believed it was to put diabetes clinicians and basic scientists together in coordinated laboratories. One day, Williams brought up this idea of a collaborative research approach with his patient and friend Senator Warren Magnuson, who happened to be a frequent champion of health-related legislation.

This conversation and many others that followed prompted NIDDK’s institutional predecessor, the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, to dedicate funding towards establishing a group of Diabetes and Endocrinology Centers.

After a competitive grant review process, Vanderbilt University became the first funded Diabetes-Endocrinology Research Center in 1973. When more funding was made available, three additional centers soon followed – the University of Washington in Seattle, Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, and Washington University in St. Louis.

Today, 17 Diabetes Research Centers continue to deliver on the same founding mission that Williams envisioned. Each center provides an integrated program of diabetes research to support cutting-edge basic and clinical research with the goal of rapidly translating research findings into novel strategies for the prevention, treatment, and cure of diabetes and related conditions. Importantly, the Diabetes Centers work together and with other NIDDK-funded center programs, including the Cystic Fibrosis Research and Translation Centers and the Centers for Diabetes Translation Research, to best leverage resources and collaborative opportunities.

To commemorate the 50-year milestone, the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center and its director, Dr. Alvin Powers, organized two special events including the Vanderbilt Diabetes Day in April and a special session during Vanderbilt’s NIDDK Medical Student Research symposium in July. Former NIDDK Director and Vanderbilt alumnus, Dr. Phillip Gorden, received the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center Lifetime Achievement Award in April. The special July session, which included DRC directors and researchers, was focused on building the physician researcher pipeline in endocrinology.

Drs. William Cefalu, NIDDK; Griffin Rodgers, NIDDK; Philip Gorden, NIDDK, retired; and C. Ronald Kahn, Joslin Diabetes Center, at the Vanderbilt Diabetes Day symposium in April.

Drs. William Cefalu, NIDDK; Griffin Rodgers, NIDDK; Philip Gorden, NIDDK, retired; and C. Ronald Kahn, Joslin Diabetes Center, at the Vanderbilt Diabetes Day symposium in April.NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin Rodgers participated in both events, along with Drs. William Cefalu, Corinne Silva, and Art Castle from NIDDK’s Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic Diseases.

“I was honored to attend these celebratory events and interact with medical students interested in diabetes research,” said Rodgers. “Our diabetes research centers have provided so much information and training that benefit individual patients and populations with diabetes, with respect to better diagnosis and treatment, and increasingly, prevention of the disease. I look forward to what they’ll achieve in the years to come.”

Celebrating 40 years of DCCT/EDIC

By Alyssa Voss

Accessible Image Description

(Left to right) Dr. Bruce A. Perkins, Study Vice-chair and Principal Investigator, University of Toronto Center, Toronto, Canada; Dr. Ionut Bebu, Co-Principal Investigator, Data Coordinating Center, The George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health; Dr. Rodica Pop-Busui, Co-Investigator, University of Michigan Center and ADA President for Medicine and Science; Dr. Barbara H. Braffett, Co-Principal Investigator, Data Coordinating Center, The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health; Dr. John Lachin, Co-Principal Investigator, Data Coordinating Center, The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health; Gayle Lorenzi, Co-Chair, Coordinators Committee, and Community Health Project Manager, University of California San Diego; Dr. Rose Gubitosi-Klug, Principal Investigator, DCCT/EDIC Clinical Coordinating Center, University Hospitals Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital Case Western Reserve University; Catherine Martin, Co-Chair, Coordinators Committee, University of Michigan School of Nursing; Dr. Ellen Leschek, Project Scientist, NIDDK; and Dr. David Nathan, Study Chair, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Not every day can a person say they helped change modern medicine, but staff and participants involved in the NIDDK-supported Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) got that opportunity in June at the 83rd American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s Scientific Sessions in San Diego.

In a symposium marking the 40th anniversary of DCCT and its long-term outcome study, the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study, a panel of study investigators, including study chair Dr. David M. Nathan, director of the Diabetes Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, and NIDDK project scientist Dr. Ellen Leschek, gave tribute to the study’s participants and its long-lasting impact on type 1 diabetes treatment and people living with the disease.

Thirty years ago, in 1993 and after 10 years of study, the initial DCCT study results were presented at the ADA Scientific Sessions in Las Vegas. For the first time, the study demonstrated that early-stage complications of type 1 diabetes could be reduced by between 35-76% through intensive management of blood glucose levels. The New England Journal of Medicine published the primary findings in 1993, and the paper remains among the most highly cited in diabetes literature to this day. In total, DCCT/EDIC has published nearly 400 papers, each helping to advance understanding of type 1 diabetes and its complications.

The primary results of the DCCT were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 1993.

The primary results of the DCCT were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 1993.DCCT and the glucose hypothesis

The DCCT was recommended to Congress in 1975 by the National Commission on Diabetes to test the “glucose hypothesis”– the idea that targeting diabetes treatment to bring blood glucose levels as close to non-diabetic levels as possible would prevent or delay long-term complications of diabetes.

Dr. David Nathan, DCCT/EDIC study chair, presents at the 83rd ADA Scientific Sessions in June.

Dr. David Nathan, DCCT/EDIC study chair, presents at the 83rd ADA Scientific Sessions in June."At the time, diabetes was the third leading killer in the United States, with incidence rates on the rise, and most people with diabetes died by their late forties. By testing the glucose hypothesis, we hoped to improve the quality of life and reduce significant complications including blindness, kidney failure, stroke, amputation, and heart attack for people with diabetes," said Nathan.

And so it began. In 1983, the DCCT launched at 21 centers across the United States, later expanding to 28 centers and enrolling 1,441 people between ages 13 and 39 with type 1 diabetes, with an average age of 27. One-half of those enrolled received intensive diabetes treatment, which involved three or more daily injections of insulin or use of brand-new insulin pump technology; four or more blood glucose tests daily; monthly visits with study investigators with frequent phone calls between visits; and the goal hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of less than 6.05%. The other one-half of participants received conventional diabetes treatment, which involved one to two daily injections of insulin; blood or urine glucose testing daily with no specific glucose targets; and one visit with study investigators every three months.

After six and a half years, the intensive therapy group maintained HbA1c levels around 7%, compared to around 9% in the conventional therapy group. The difference produced dramatic results. Compared to conventional therapy, intensive therapy reduced the development of diabetic eye disease by 76% among participants with diabetes for less than five years; the progression of diabetic eye disease by 54% among participants with diabetes who already had signs of retinopathy; and the development of kidney and nerve disease by 43% and 57% respectively. Glucose control was the dominant factor underlying these benefits.

The news of these findings had immediate translational effects. The ADA sent a letter to 40,000 clinicians in the United States to update the standards of care for type 1 diabetes. In addition to changing clinical practice, DCCT also spurred decades of new research avenues to improve diabetes management. Innovations in diabetes care included the development of insulin analogues, new insulin delivery methods, treatment algorithms, and other new technologies, all to further improve blood glucose levels with less risk of hypoglycemia and to make intensive therapy more accessible.

EDIC and the lesson of metabolic memory

At the end of DCCT, the study team transitioned the cohort to the EDIC long-term study in which participants would visit study clinics annually. Participants in the conventional therapy group were taught intensive glucose management, and all diabetes care was transferred back to their own clinicians. HbA1c levels quickly steadied at about 8.0% in both DCCT treatment groups. During EDIC, the team expected participants to reach ages and duration of diabetes that would allow for the study of more advanced complications including cardiovascular disease.

After four years, the EDIC study demonstrated ‘metabolic memory,’ in which the effects of the original treatments persisted even after the HbA1c levels had become similar in both treatment groups. This finding further reinforced the clinical recommendation to start intensive therapy as early in the course of type 1 diabetes as possible.

As EDIC continued, ongoing analyses elucidated the crucial role of glycemic control and HbA1c in promoting long-term health and preventing serious diabetes-related conditions. From the first analyses looking at diabetes-related complications, HbA1c was the single most important modifiable risk factor for microvascular and cardiovascular disease. And more recently, analyses have shown that intensive therapy and glycemic control play important roles not only in preventing severe complications but also in maintaining cognitive health, hearing function, mobility, and skeletal health.

“The implications of these findings are so important because it means it’s never too late to improve glycemic control. Lower HbA1c has a durable effect over time, and intensive intervention should be started as early as possible after diabetes diagnosis because having better control – even if delayed – helps prevent or slow the development of all outcomes we’ve studied in EDIC,” said panelist Dr. Bruce Perkins, study vice chair and professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, Canada.

Long-term follow-up in EDIC has also shown that the increased risk of death that had accompanied type 1 diabetes in the past had also been eliminated by intensive therapy. The original intensive therapy group's rate of death is now no different than that of the general population. This result clearly showed that intensive diabetes therapy made a meaningful impact on preventing serious life-threatening complications and extending length of life in people with type 1 diabetes.

The next phase of EDIC will examine the effects of long-duration type 1 diabetes in its aging population. The average diabetes duration of EDIC participants is now 42 years and their average age is 63, a time at which age-related issues commonly arise. In addition, the proportion of the cohort with overweight and obesity is similar to the general population. EDIC will now look at the interaction of diabetes-related conditions and complications, weight-related issues including liver disease and sleep apnea, and age-sensitive factors including heart failure, cognitive and physical function, self-care, health economics, and quality of life.

Dedicated participants for the long haul

DCCT/EDIC study participants and staff from UC San Diego enjoy a special photo opportunity at the 83rd Scientific Sessions.

DCCT/EDIC study participants and staff from UC San Diego enjoy a special photo opportunity at the 83rd Scientific Sessions.DCCT/EDIC is well-known for its steadfast group of dedicated study participants, who remain the largest type 1 diabetes study cohort retained for the longest time. Likewise, its dedicated staff and study coordinators, credited with much of the retention success, have remained committed to the study, many for decades. The majority of participants have remained engaged over the last 40 years, and today, 90% of surviving cohort members are still enrolled. EDIC has studied them for 60% of their lifespans and about 90% of their time with diabetes.

The more than 1,000 remaining participants travel from across the United States, Canada, and as far as Europe, the Middle East, Australia, and New Zealand to complete their study visits at one of the remaining 27 clinical centers. They have completed more than 120,000 study visits.

The cutting-edge tests, annual evaluations, and desire to help others are among the reasons participants give for being involved in the study for so long.

“I am so appreciative to be able to be part of the study, to get my test results and monitor my health, and to be at the cutting edge of what’s new with diabetes management,” said Elizabeth Murphy who's participated in the study for 39 years and attended the ADA session.

More contributions to modern medicine

Equally important to advancing the understanding of diabetes complications, DCCT/EDIC has been instrumental to the development of innovative screening techniques and fine-tuning screening schedules.

Recently, the team reported new methods for diagnosing cardiovascular nerve damage and other microvascular complications, made possible by analyzing the multiple measurements taken at different points during EDIC. By assessing changes over time, the study was able to show which patients were at risk for developing these complications.

DCCT/EDIC has used its robust data to inform personalized, evidence-based screening guidelines across the lifespan from adolescence to adulthood, for retinopathy and more recently, kidney disease. Personalized screening schedules are now also incorporated into diabetes standards of care, which help identify how frequently or infrequently people with diabetes need screening, often minimizing the screening burden and need for tests.

The study has also influenced how clinical trials are conducted and set a precedent for implementing NIDDK-funded multi-center clinical trials and designing patient-oriented research. DCCT/EDIC created a network of diabetes clinicians and researchers that grew and generated many fruitful scientific ideas and opportunities. The network stimulated further NIDDK research on diabetes that yielded groundbreaking results, including the Diabetes Prevention Program, TrialNet, LookAHEAD, TODAY, GRADE and RISE.

“I cannot overstate the enormous impact of the DCCT/EDIC study,” said NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers. “The entire diabetes community is forever indebted to the dedicated participants who made the study possible and the study team, whose endless energy and commitment keep propelling the research forward.”

Researchers interested in accessing data from DCCT/EDIC may visit the NIDDK Central Repository.

NIDDK's Central Repository earns seal for trustworthy data

NIDDK’s Central Repository received the CoreTrustSeal certification in July, only the fourth among NIH-associated repositories and one of 160 certified repositories globally. The CoreTrustSeal certification demonstrates the quality, transparency, and trustworthiness of the NIDDK Central Repository to data stewards, such as scientists who submit data to the repository and the broader research community. To be certified, repositories must meet 16 mandatory requirements reflecting their trustworthiness and sustainability characteristics, which include quality, preservation, authenticity, ease and effectiveness of data reuse, and more.

The Repository, with support from NIDDK and NIH’s Office of Data Science Strategy, has implemented several system enhancements to support FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) of data and biospecimens. The Repository will continue to improve resource usability and access in alignment with NIH and NIDDK strategic plans to make it easier for scientists to find, access, and reuse previously collected data and samples, thereby maximizing the reach of resources and their impact on health research.

Editors’ note: Read recent Director’s Update stories on the Central Repository: Researchers leverage NIDDK resources through the NIDDK Central Repository, NIDDK celebrates two decades of data sharing.

Special Diabetes Program and NIDDK research highlighted in U.S. Senate hearing

Witnesses for the JDRF Children’s Congress hearing included (back, left to right) NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin Rodgers, JDRF CEO Dr. Aaron Kowalski, music producer and philanthropist “Jimmy Jam,” and (front, left to right) JDRF Children’s Congress delegates Maria Muayad and Elise Cataldo

Witnesses for the JDRF Children’s Congress hearing included (back, left to right) NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin Rodgers, JDRF CEO Dr. Aaron Kowalski, music producer and philanthropist “Jimmy Jam,” and (front, left to right) JDRF Children’s Congress delegates Maria Muayad and Elise CataldoIn July, NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations on type 1 diabetes research advances and opportunities. The hearing, “Accelerating Breakthroughs: How the Special Diabetes Program Is Creating Hope for those Living with Type 1 Diabetes,” was led by Committee Chair Patty Murray (D-WA) and Vice Chair Susan Collins (R-ME) and was held in conjunction with the JDRF Children’s Congress. Around 165 Children’s Congress youth delegates from all 50 states and five other countries attended.

Rodgers’ testimony highlighted groundbreaking research discoveries made possible with support from the Special Diabetes Program, such as developments in artificial pancreas technologies that greatly ease the burden of diabetes management. Also testifying were JDRF CEO Dr. Aaron Kowalski, music producer James “Jimmy Jam” Harris, and Children's Congress delegates Maria Muayad and Elise Cataldo who shared their lived experiences with type 1 diabetes.

“The Special Diabetes Program… has ushered in a new era where individuals with type 1 diabetes have significantly improved health, longevity, and, importantly, quality of life,” said Rodgers in his testimony. “With continued research, we hope to move even closer to the day that all people can be free from the burden of type 1 diabetes and its complications.” Read his full testimony here.

JDRF Children’s Congress delegates gather on the steps of the House of Representatives, along with NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin Rodgers and others.

JDRF Children’s Congress delegates gather on the steps of the House of Representatives, along with NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin Rodgers and others.New NIDDK-funded study seeks to understand weight regain

The struggle is real for so many people who lose weight but have tremendous difficulty keeping it off. Now a new NIH-funded study aims to explain why.

The Physiology of the Weight Reduced State, or POWERS study, will provide a lifestyle intervention with trained clinical staff to help participants with obesity lose weight and then follow them over a 12-month weight maintenance period. Participants will provide biospecimens and questionnaire data that will allow the research team to analyze the various potential behavioral, metabolic, cellular, and molecular factors involved in maintaining a reduced weight. “We hope the study will provide the medical community a better understanding of the major contributors to weight maintenance after weight loss to help improve and potentially individualize approaches to weight loss and weight maintenance,” said Dr. Maren Laughlin, co-director of the NIDDK Office of Obesity Research.

The study, funded by NIDDK and the NIH Office of Disease Prevention, will enroll people ages 25 to 60 years with a BMI between 30 and 39 and no history of diabetes.

To find out more about POWERS, visit www.powers-study.org.

Getting to Know: Dr. Mary Evans

Dr. Mary Evans is a program director for special projects in nutrition, obesity and digestive diseases in NIDDK’s Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition. She spoke with Heather Martin about her educational journey and fascinating work at NIDDK.

How did you get into the field of nutrition and obesity?

I was always interested in many aspects of science. I majored in chemistry and went to graduate school to study nutrition. I also have been an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), a clinical lab scientist, a bench scientist, and a clinical trials specialist. Each experience taught me something new and different and eventually prepared me to come to NIH in 2006 to work on Look AHEAD, a long-term, multi-center clinical trial to study health effects in a weight loss program.

As a member of the Working Group that recently published NIDDK’s “Pathways to Health for All: Health Disparities and Health Equity Research Recommendations and Opportunities,” can you share about the report and how researchers can apply a health equity lens to their work?

“Pathways to Health for All” makes recommendations NIDDK could pursue to improve health equity and reduce the health disparities that exist for so many NIDDK diseases. I participated in the workgroup along with other NIDDK staff, external researchers, and community members including patients and caregivers with lived experience with the diseases in NIDDK’s mission.

It’s clearer than ever that we must apply a health equity lens to our work, which means using language and acting in a way that is inclusive, elevating community members as partners rather than research participants, and getting their input at all levels of research, from study conception to design, implementation, and dissemination.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

I love being able to work on high-impact programs and projects that are at the forefront of nutrition and obesity research. As the program officer for the NIDDK-supported Nutrition Obesity Research Centers (NORC), which consists of 11 centers across the United States, I oversee the program that provides infrastructure support and other resources to make nutrition and obesity research more cost-effective and sustainable. And I’m a co-chair for two implementation working groups for the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research to improve methodologies that assess what people are eating and to enhance diversity, equity, and inclusion in the nutrition workforce. One initiative, called BRIDGES, is a new collaborative program to support scholars in nutrition- and obesity-related research.

Editors’ note: Read more about BRIDGES in this issue of the NIDDK Director’s Update.

What advice do you give to people interested in a research career?

Find a topic or question that you find exciting and meaningful and run with it – but also be open to your research going in a different direction. Get to know people and see where it takes you. Talk to scientists, NIH staff conducting or overseeing research you are interested in, and community leaders, and seek out advisors who are committed to your professional and personal growth. Networking and mentoring are critical for success in your research career.

What are your interests outside of NIH?

I am a novice cello player and avid sports fan. I especially follow Washington, D.C. hockey, baseball, and soccer teams.

Strengthening the scientific workforce with BRIDGES

While scientific talent is well-represented among people from all backgrounds, opportunity is not. From graduate students to faculty and beyond, the biomedical research workforce does not reflect the makeup of the U.S. population. Despite long-term efforts to bridge this gap and provide opportunities for communities underrepresented in scientific research, progress has been slow, demonstrating the need for intensified efforts and innovative strategies. That is where BRIDGES comes in.

BRIDGES, or “Bringing Resources to Increase Diversity, Growth, Equity and Scholarship in/for Obesity, Nutrition, and Diabetes Research,” is a new NIH-funded consortium designed to improve the success rate of underrepresented ethnic minority scientists competing for federal research funding and increase the diversity of the overall research workforce. Through professional development, mentoring, networking, and pilot funding opportunities, the program empowers post-doctoral fellows and early career faculty to pursue successful careers in nutrition, obesity, diabetes, and related fields. BRIDGES scholars will explore new ideas and generate preliminary data to leverage for larger grant funding applications. At the end of two years, they will develop an NIH grant proposal appropriate to their career stage, either a Career Development Awards (K series) or Research Grants (R series).

The consortium comprises four independent but collaborative programs called COURAGE, LAUNCHED, LIFT-UP, and SPLENDOR NC. Together, the consortium represents more than 19 universities working together and building networks that foster career development opportunities for nutrition, obesity, and diabetes scholars from diverse backgrounds.

Funded by NIDDK, the NIH Office of Nutrition Research (ONR), the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences (OBSSR), the Office of Disease Prevention (ODP), and the Chief Officer of Scientific Workforce Development (COSWD), BRIDGES reflects a shared vision of promoting diversity and research excellence among the scientific research workforce. For more details about the consortium, please visit: www.norccentral.org/bridges

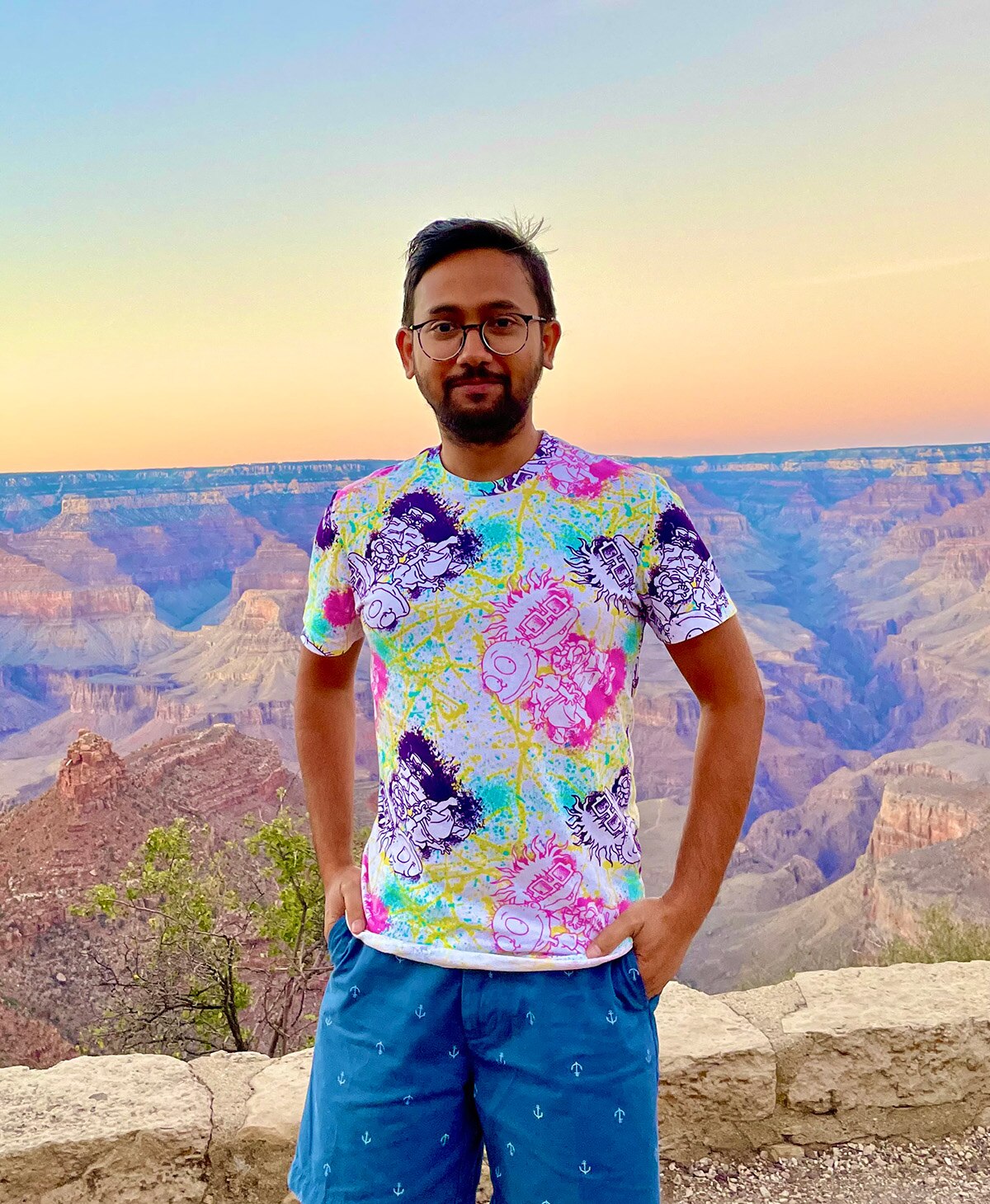

Fellow Spotlight: Dr. Shubhra Jyoti Saha

Name: Shubhra Jyoti Saha

Hometown: West Bengal, India

Current position: Visiting Fellow in Dr. Ross Cheloha’s lab, Chemical Biology in Signaling Section, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry

What inspired you to pursue a research career?

I am fascinated with the transformative power of organic chemistry in drug discovery. During my master’s dissertation, I delved into the captivating world of organic small molecules and witnessed their evolution as promising drug candidates.

A pivotal moment in my inspiration came when I learned about the adverse effects of a drug known as a thalidomide isomer. This revelation opened the door to a world of profound consequences and the crucial importance of understanding stereochemistry in drug development. Learning more about the long path of trials and approvals required for a newly discovered molecule to become a life-saving drug provided me with insights into the arduous journey that leads to medical advances.

By embarking on a research career, I hope to play a pivotal role in advancing the frontiers of drug development, unraveling new therapeutic avenues, and ultimately making a meaningful difference in the world of healthcare.

What public health problem do you ultimately hope to solve with your research?

I aim to address the critical public health problem of improving HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, control and eradication. Despite the advent of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) as the standard of care against HIV-1, drug toxicity and the emergence of drug resistance pose significant challenges to effectively combating the virus.

Moreover, certain disproportionately affected populations, including gay and bisexual men, transgender people, and communities of color continue to bear a disproportionate burden of new HIV infections. The persistence of stigma and discrimination associated with HIV further hinders prevention and treatment efforts, exacerbating the public health impact of the epidemic.

My goal is to contribute to the development of safer, more effective anti-HIV drugs that address limitations of current treatments. I recently received the NIH Intramural AIDS research fellowship from the Office of AIDS Research to pursue this goal. I aim to improve the quality of life for those living with HIV and help reduce new infections, especially within communities who are disproportionately affected. By breaking down barriers to effective prevention and treatment, I hope to make a meaningful contribution to global public health by combating HIV and promoting equitable healthcare for all.